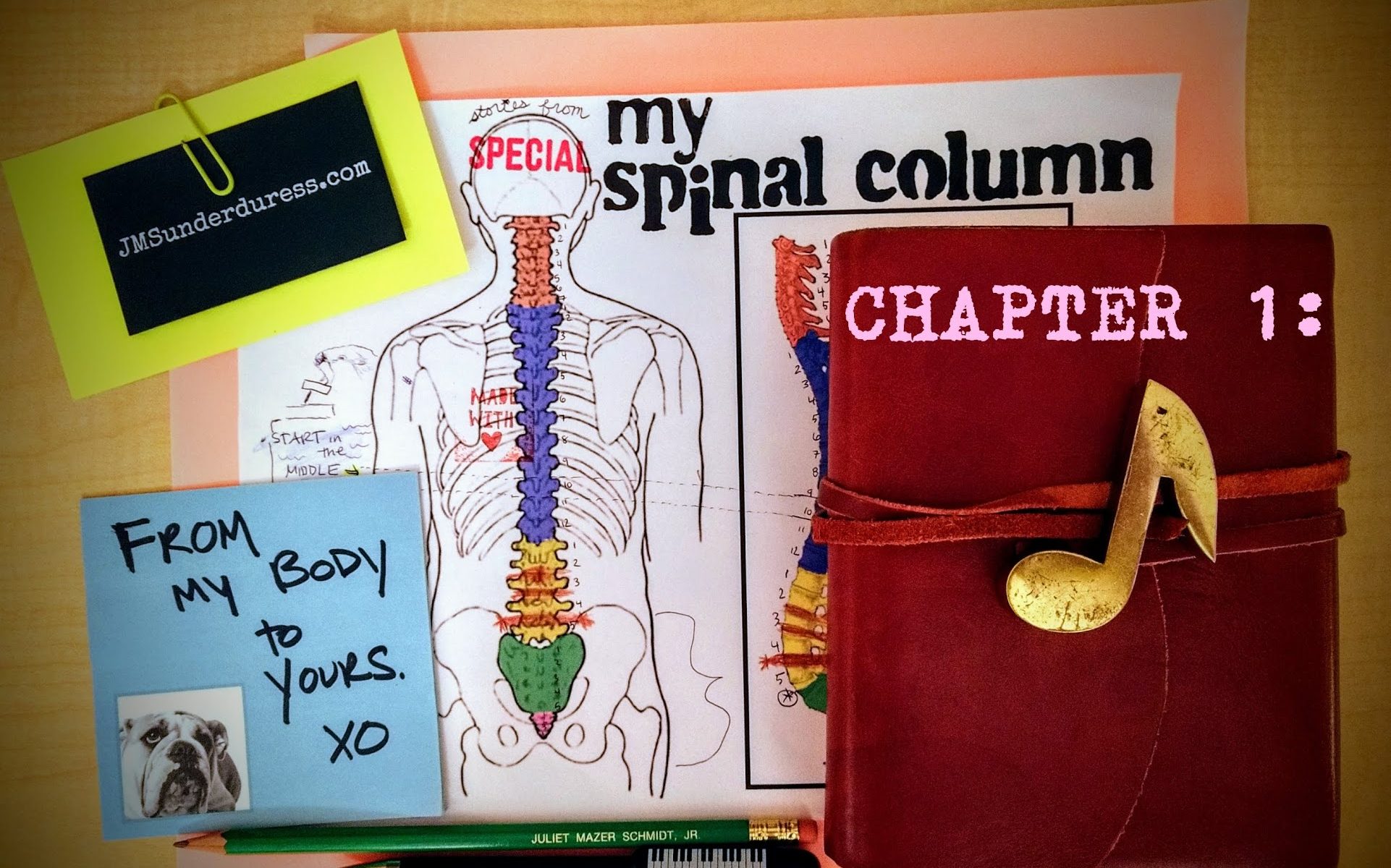

MY SPINAL COLUMN is an ongoing series. To start at the very beginning (a very good place to start), click HERE.

A season later, Tony’s blood splatter still stains my clothes.

Slung over one end of our banister, (the other now doubling as ballet barre), sunlight from the alleyway sometimes catches crimson streaks in a spontaneous spotlight shaped from barbed wire fencing and window bars, filtered further through fat leaves of the housewarming Croton that climbs our sill. Each new layer of growth marks passage of time in my New York life, slowly but steadily eclipsing the metallic obstacle course just outside.

I focus with the light, my eyes returning to the buttonless, black cardigan; dark jeans, still rolled at each ankle; white tank, sliced sideways by thin stripes of various greys – from the couch it resembles lines of small lettering I can’t quite read. The story behind these three textiles taunts me: “LUCKY YOU” deems the denim’s branded fly, a label I’ve come to interpret anew ever since this fabric met Broadway Theatre Seat A101, and the contents of Isaac Powell’s blood pack, on the evening of March 11, 2020.

Earlier that afternoon, I’d attended what would be my last in-person Japanese class for the term, followed by what would be my final in-person coffee date for the foreseeable future. Sensing calm before a storm in both spaces, I’d walked west across Manhattan, weaving my way through the mid-block pedestrian tunnels lesser-known by tourists, craving the familiar landscape of theater lights before heading north.

Stopping at an ATM en route to Columbus Circle, a marquee across the Avenue caught my eye: memories of my first paid theater writing gig (promoting a two-ton puppet) pulled me to the Broadway’s box office window where, not three hours before curtain, I traded two twenties for a single rush seat to Ivo Van Hove’s condensed reimagining of a classic dance-driven rivalry now playing on Kong’s former stomping grounds.

I’d been on the fence about these Sharks and Jets, recalling the glossy “SOMETHING’S COMING” flyer in our mailbox last fall, its design centered around chain link and tattoo art – I’d heard much of Jerome Robbins’s renowned choreography had been cut, replaced with multimedia elements to simulate security camera footage.

My gut reaction, unpredictably, had been pity for Ivo: did he not feel the punctuation of Robbins’s choreography, synced perfectly with Leonard Bernstein’s beats? A snap. A sharply turned head. A rib cage isolation. A hip pop. A knee bent when it shouldn’t. The tension, the aggression, the chemistry, the war: IT WAS ALL RIGHT THERE, IN THE DANCING, did he not see?! On the afternoon of March 11, COVID in the air, curiosity got the best of me: a highly-publicized production boasting 32 Broadway debuts, I decided to find out what Ivo did see in West Side Story.

Following a sunset walk through Central Park, mom’s voice in my ear from Michigan, I headed back to the Broadway. From the front row’s House Right center aisle, my feet tapped along to woodwinds warming up Bernstein’s famous melodies – my sneaker tips inadvertently brushing the wall of the orchestra pit. I digested Playbill bios (we’d have a Standby in for Riff), as audience members around me chatted nervously, describing stressful and surreal work days: offices closing, rumors of transit shutdowns and upcoming quarantine, meetings to train on “something called ‘Zoom.’”

The show emerged from stillness: actors took their places in a downstage lineup, as a camera panned down the line, closeup footage of each face projected larger-than-life upstage. I confess: despite the months of hype, I found myself floored less by the ambitious production elements, far more by the bodies that fought and fell in love inches from mine. Moreover, I couldn’t remove the reality of what loomed for us all: will this be the last show? Are you OK? ARE YOU BEING TAKEN CARE OF?!

“Tony” died dramatically in a heavy rainstorm just shy of 10PM, stage blood spraying my face; “Maria” passionately cast her scripted blame on all bodies present, as a sticky wetness settled onto patches of my skin, small puddles forming in crevices of the coat I’d stuffed strategically at the base of my spine to secure loose sacroiliac joints.

After curtain call, I chatted briefly with an usher – kindly informing that the corner of Seat A101 had been hit with a healthy coating of dyed corn syrup, reassuring that the patron seated there (me) was unscathed. I declined an offer for dry cleaning reimbursement, cracking a joke about my “free souvenir”: we talked a bit of shop, both anticipating stressful times ahead for House Staff – my laundry need not add to the list.

Outside, I bumped into a former Broadway colleague: we spoke of our own musicals, musicals on which we’ve worked – the musical we’d both just seen (I shared the startling experience of being “shot” mid-show, my black parka glistening under the streetlights). Our conversation closed on the Coronavirus: …would Broadway shut down?

It would, indeed – the very next day, 5PM.

My first experience sharing air with any staged production of West Side Story, the occasion also marks my final-for-now live theater experience – also the production’s final-for-now performance. Undressing in our doorway that night, contemplating COVID-closures on the horizon, the day’s wardrobe became a trio of provisional Post-Its, stage blood a theatrical Rorschach test triggering complicated feelings I cannot yet fully articulate, nor shake, on the unraveling state of American theater.

For a massive community of NYC-based theater professionals, my household included, Thursday, March 12 marked the start of an indefinite “intermission”; many have since boxed up their belongings and left the City, return dates TBD. We discuss dinners we’d like to host, once it’s safe – stung by the sad realization that more than half of our presumed guests now reside thousands of miles away.

Having left a career in criminal litigation to pursue theater work seven years ago – now several hundred theater experiences (and a divorce) on the other side of that decision, the lack of live theater in my life leaves a hole words cannot fill.

Theater-makers wrestle constantly, each in our own style, with relevance and worth. Add a global pandemic that categorizes the industry (correctly) as “Non-Essential,” and the degree of difficulty escalates well beyond basic self-doubt and inner-demons.

For worse (financially) and for better (nearly every other aspect), I got a slight head-start swimming the waters of occupational uncertainty, having left my agency over the winter to address advancing health issues – the election of “self-care” an outlier in my 36-year run of overachieving, workaholic trends. With COVID’s crash landing coming so soon thereafter – before I could see my next step let alone take it, quarantine’s freefall has led back to a familiar, if surprising territory.

Ballet was not the plan – until it became the plan: an aimless Monday afternoon Instagram scroll in April led me to a live ballet class, led by New York City Ballet Principal Dancer Tiler Peck, dancing from her parents’ kitchen in Southern California. On instinct, I started dancing along – barefoot in our bedroom, still in boxers and an oversized sleepshirt. Toward class end, Brazilian ballerina Carla Körbes “joined” to walk several hundred students through the technique behind “swan arms” (which Carla does better than anyone – seriously, look her up).

Discovering that Tiler taught a free class daily, I tuned in again on Tuesday – this time in sports bra and shorts, hair pulled back, old ballet slippers resurrected from their sleeve in my dance bag (small “JMS” in black Sharpie – Mom’s handwriting – still on the bottom of the pale pink soles!). Musician extraordinaire John Batiste “joined” midway, to sing and play piano (“Don’t Stop”), while students danced steps Tiler had pieced together in time with the song. (Tiler’s musicality is second to none in contemporary ballet, the Company co-founded by Jerome Robbins a perfect playground for her talent.) Wednesday’s class brought the music of Disney and three musical guests: Liz Calloway, Derek Klena, Christy Altomare each lent their voice via Anastasia songs, as dancers around the world spun in whatever space they had available.

Monday through Saturday, I’ve taken every #turnitoutwithTiler class since – learning early on that Tiler had only recently returned to City Ballet, following a neck injury that had taken her out of the Company’s previous season. Training each day, if invisibly, with a professional who understands both work ethic and the necessity of listening to messages sent through muscles and nerves, I’ve come to feel less alone in my healing body, less afraid of it.

Diving further into ballet documentaries and Internet footage, a pattern emerges: nearly every dancer I “meet” manages daily discomfort, most having overcome at least one severe injury – turning inward, coming back to the barre, taking the time to transmute pain into grace, magnificence, and a more mature understanding of their body. I aspire to do the same, if only from my living room.

Every afternoon at 1PM, I step up to our banister for an anatomical roll call in the broken French I’ve known since childhood: plié and relevé leading to tendu, first then fifth; dégagé into fondu, rond de jambe, and frappé; a finale of passé, développé and grande battement before graduating to “center” – which is where the real fun starts.

Even after class, I can’t stop moving: eager to unearth what stories my limbs still contain, I arrange the standing mirrors we buy in our local Dollar Tower and explore: I revisit my memories in movement, creating amended versions of the many shapes my body’s been called upon to make through the years by a variety of choreographers – pleasantly surprised by the pieces left still in my sandbox. I’ve filled two new notebooks since April, solely on dance.

More than once, I’ve closed my eyes and attempted to remember entries from the sketchpads of Jerome Robbins, displayed two years ago at The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts on Lincoln Center’s campus. In 1971, Robbins had pieced together his life into a series of 24 accordion journals, also containing ticket stubs, dried flowers – and drawings: he described the collection as a portal into how he saw the world as an artist, noting that New York City often felt like “a lone man walking.” I had wandered into the exhibit following a visit to the TOFT Archive (to watch Vanessa Redgrave perform Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking), and wound up spending the rest of my day digesting each of the exposed diagrams: but a few fancy buildings over from where Robbins’ Company performs, these dog-eared, squiggle-covered pages would evolve into Dances at a Gathering, The Goldberg Variations – even some legendary power struggles between Jets and Sharks.

During my visit, I overheard other guests describe the same pages as “the work of a lunatic.”

It was there, in that gallery, where I learned West Side Story had made its original Broadway debut at the Winter Garden on my birthday (September 26 – albeit 26 years earlier). Coincidentally, the Winter Garden’s latest tenant (School of Rock) had precipitated my move to New York – it was, in fact, the stage on which my partner performed at the very moment I realized the connection.

Now settling into the summer of 2020, movements of my New York life have been reduced to a lone woman, dancing – and “work of a lunatic” is most certainly part of my inner-demon’s favorite refrain.

I remain deeply grateful to Robbins for daring to share his raw footage – the “lunacy” that pulls new art from the void of the unknown. I cite Robbins, and West Side Story, as proof that shapes in the mind can have tremendous value – but the path from scribbled pages to famous stages is a long and murky one, made clearer when we’re lucky to find others dancing on our frequency.

With no dinner guests on the horizon, I’ve overtaken our living room: two Marley mats reign, while our rug rests rolled against a keyboard stand. I write late into the night, sometimes all night, working my way toward words to express my feelings on theater, on my future place in it.

For now, I’m still largely at shapes and scribbles, partial lyrics and monologues – undoubtedly “lunacy” to any who cross my notes in their current state. And so, I return to the barre daily, still on the road to healing – and lately, when I dance, my center wants to hold.

Today the City hosts heavy rain and thunder, lightning flashes in lieu of any sunlight-fueled lighting design. From behind the keyboard, my body practices port de bras to the rhythm of thunder strikes, invoking images of choreographed street fights – alternative sequences to the one that led to Tony’s death, to the stained clothes still hanging in the corner…

I look through the Croton leaves, focusing for once on the concrete alleyway – now a “stage,” and wonder: how many bodies would fit, comfortably enough to leap and turn?

I challenge myself to picture it, all of it, in vivid detail.

…When I do, comes the greater challenge: to feel truly, incredibly lucky.

TURN TO CHAPTER 2: MUSIC OF THE FIGHT

More JMSunderduress you may enjoy…

ON TURNING 35: CHILDREN AND ART (PART ONE)