Childhood Heroes I Needed…and Met as an Adult

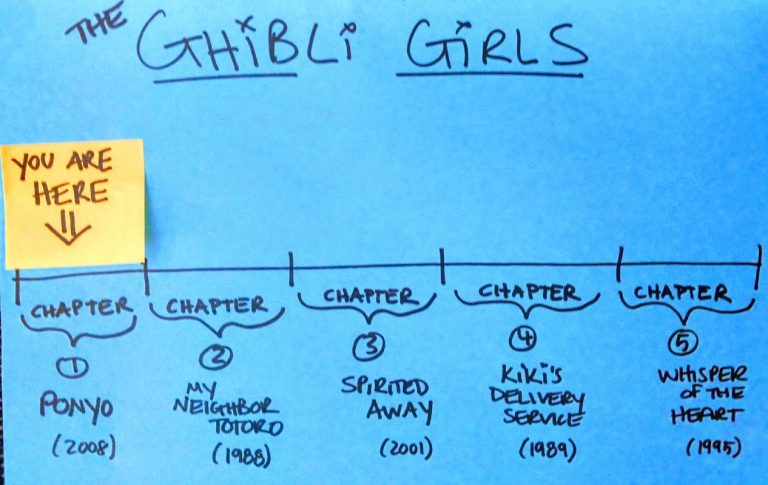

(a series in five chapters)

I mentioned in my introductory post that Studio Ghibli posts were coming…

PROLOGUE

Outside my building last week, I passed a pretend kitchen left curbside – one not entirely unlike the Fisher Price model I played with in my basement back in the ‘80s: There it sat, abandoned in the shadow of a streetlight’s spotlight, surrounded by trash. I treated myself to a moment of nostalgia: some kid on my block finished that chapter of childhood today, I thought. Too bad: it’s a good chapter, the one with pretend kitchens.

There it sat, abandoned in the shadow of a streetlight’s spotlight, surrounded by trash. I treated myself to a moment of nostalgia: some kid on my block finished that chapter of childhood today, I thought. Too bad: it’s a good chapter, the one with pretend kitchens.

Then, this morning: I saw a cheap but well-worn skateboard stuffed into a nearby trashcan – complete with Ariel and Belle stickers on its underside! Some local Disney-loving skateboarder has moved on to whatever chapter comes next – hopefully to include a better skateboard.

Another nostalgia-laced flashback: I once had a similar starter-skateboard – one from which I, too, “graduated.”

A consequence of summertime’s easier living: kids grow – and, in doing so, outgrow all kinds of childhood wonders.

A consequence of summertime’s easier living: kids grow – and, in doing so, outgrow all kinds of childhood wonders.

I’ll admit: the idea of “expiring childhood” had been on my mind already, no doubt, in-part, due to a recent viewing of newly-released Eighth Grade, Bo Burnham’s debut film featuring a breakout performance by Elsie Fisher as 13-year-old “Kayla Day.” (Highly Recommend.)

Though written and directed by a man – more than twice his protagonist’s age – Kayla’s character arc reveals a raw, cringe-inducing, “the-call-is-coming-from-inside-the-house” – no, wait – from inside your own brain! portrayal of Eighth-Grade-Girl. A sharp contrast to the charming “Pretend Kitchen” and “Disney-Princess-Stickered Skateboard” chapters of childhood, the American Middle School experience is just about the worst – with a cruel “bonus feature” for girls, who tend to be further along in their emotional development at that age and, as a result, much more aware of their crushed hope and adolescent misery.

I grew-up, like a lot of American girls, raised on a cultural diet heavy in Disney princesses (#Belle). Also, like a lot of American girls: I grew up confused about my place in the world and what to do with the inherent power I believed I might have. Reaching “Princess” status seemed a universal goal according to Disney – but one consistently on the other side of some pretty sketchy challenges: hope to be kissed while you’re unconscious; give up your voice, then get a prince to love you; accept a life sentence in a palace prison to save your elderly, trespassing dad.

I longed for female role models who could activate their power beyond singing some secret anthem – often to no one, and certainly not within earshot of the ones who needed to hear it most. Belting “Part of Your World,” and the “Belle” reprise, and “A Whole New World” into my bedroom mirror provided a self-esteem starter-kit, sure, but I craved cartoon women who confronted the world head-on and decided their own destinies.

To be clear: I have a lifelong love of Disney culture. I think they’ve written some of the best, most influential original musicals of the past three-decades: I have seen The Lion King more than a dozen times – including during its Original Broadway Season (#HeatherHeadleyLove). I dreamed of being a Disney Princess – Hell, I even got married at Walt Disney World (and it was one of the best days of my life, no question). I believe I’ll always treasure Disney and its “royalty.” But the truth is: at no point have I ever actually felt like a Disney Princess on the inside – I just believed, based on lessons from my childhood, it was important to try. In doing so, I imitated a perfection I knew deep down I could never attain…and it left me, along with a lot of American girls, adapting to adolescent and adult life amidst a relentless mental fog of inadequacy. I wish this metaphorical mind-pollution on no one – definitely not little girls. (It’s hard enough already.)

Last year – at age 33 – I met the heroines of Hayao Miyazaki. I have no idea how this old, Japanese man has been able to capture adolescence without condescension, but he has done it. A renowned filmmaker and co-founder of Studio Ghibli (think: Japan’s PIXAR), Miyazaki’s films are works of art; his characters role models for every age.

…Oh, how I wish I could go back in time and implant the lessons of Miyazaki’s female protagonists into my younger selves: they would have been wonderful resources in countless moments of confusion and uncertainty – perhaps most of all in eighth grade.

Coincidentally, Bo Burnham seems to share Miyazaki’s gift of portraying with profound sincerity what it is to be a female figuring out her place in the world – and while I may not understand this magic they share, they write from a place that closely resembles recesses of my own childhood memories.

While watching Eighth Grade, I found myself channeling stereotypical scary-movie screen-coaching behavior (i.e. “don’t go in there!”; or, “don’t eat that food you were specifically told not to eat!”; or, “keep your pants on, Sigourney: you’re gonna have to fight an alien in, like, 90 seconds!”): I resisted the urge to shout through the screen to Kayla, “STOP WATCHING MAKE-UP TUTORIALS AND ‘HOW TO GIVE BLOWJOB’ VIDEOS: GO WATCH KIKI’S DELIVERY SERVICE!” and “GIRL, GET OUT OF THAT CAR, RUN HOME AND WATCH WHISPER OF THE HEART – WAIT FOR YOUR VIOLIN-MAKER AND HIS MUSICAL FRIENDS, KAYLA! ”— (I *promise* that last reference will make sense by the end of this series).

Kayla Day may be a character, but what I think Eighth Grade’s inevitable popularity will prove: she’s in all of us. We are, each of us, at times, that confused and uncomfortable and misled.

GOOD NEWS! Miyazaki made some stunning cinematic roadmaps to navigate such chapters, using a visual language that defies barriers and connects humanity on a primitive level.

I’d like to (re-)introduce readers to five powerful cartoon heroines that I think can make eighth grade – and all that follows – easier for everyone. Enjoy.

CHAPTER ONE

Released: 2008

Protagonist Age: 5

Appropriate Viewing for: ALL AGES!

Miyazaki’s Role: writer/director

Inspiration: Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid

Somewhere in the process of growing-up, life (over-)polishes girls into a state of such demure politeness that expressing a clear “want” becomes something we only (re-)learn decades later through therapy and/or improv classes.

Ponyo opens by telling the world, unabashedly, that she loves a boy named Sosuke – and ham.

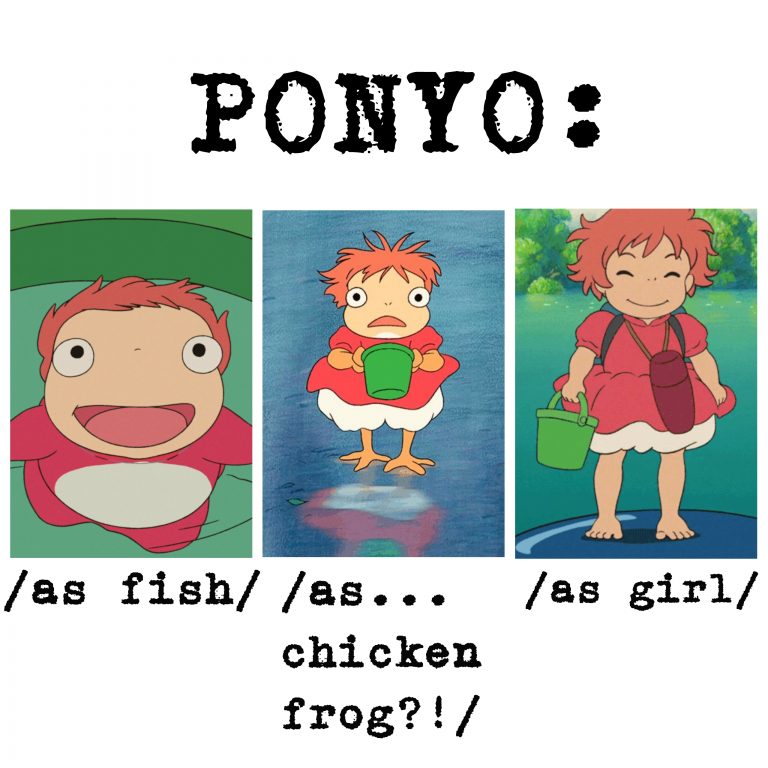

Miyazaki created Ponyo because he couldn’t accept Andersen’s premise that The Little Mermaid’s [unnamed] fifteen-year-old title character had no soul. So, he set out to create one who did: a vivacious five-year-old goldfish named Ponyo, star of a movie made for five-year-olds.

At five, children lead with their souls – they haven’t been taught not to:

Like [Ariel], Ponyo longs to explore the shore up above – something her sorcerer father expressly forbids, and a curiosity her siblings do not seem to share. She is unapologetically different and enjoys her own company; no sidekick necessary. On an unsanctioned solo adventure, Ponyo finds herself stuck in a glass bottle, washed-up on the shoreline where five-year-old Sosuke plays. On pure instinct, Sosuke successfully breaks the glass, freeing Ponyo from suffocation, then helps her back to consciousness by finding her water; Ponyo responds by healing Sosuke’s sliced finger – with literal magic. In this moment, for perhaps the first time in their lives, Ponyo and Sosuke rise up and do the things they see their parents do: magic spells are routine for Ponyo’s dad; Sosuke visits his mom regularly at the nursing home where she works.

Ponyo and Sosuke don’t combine forces to create one another’s powers, they simply help pick the locks on one another’s potential. Their connection isn’t like Captain Planet’s Planeteers or Gary and Wyatt’s Lisa-conjuring computer in Weird Science; it’s more like Guy and Girl in Once (“his songs only needed one thing – her”) –except instead of a repair shop piano, Ponyo plays on a magic-infused ocean.

But heart-following and dream-chasing come at a cost – even when you’re five and literally magical: Ponyo’s soul-driven desire to transition from fish to girl and spend her life near Sosuke disrupts the very balance between humans and nature. Her disapproving dad communicates this consequence: a former-human himself, his reaction to Ponyo’s desire for humanity reinforces the idea that converts oftentimes make the most stringent adversaries – and that parents react to their children, if instinctive and unconscious (and perhaps incorrect), based on their own life experiences.

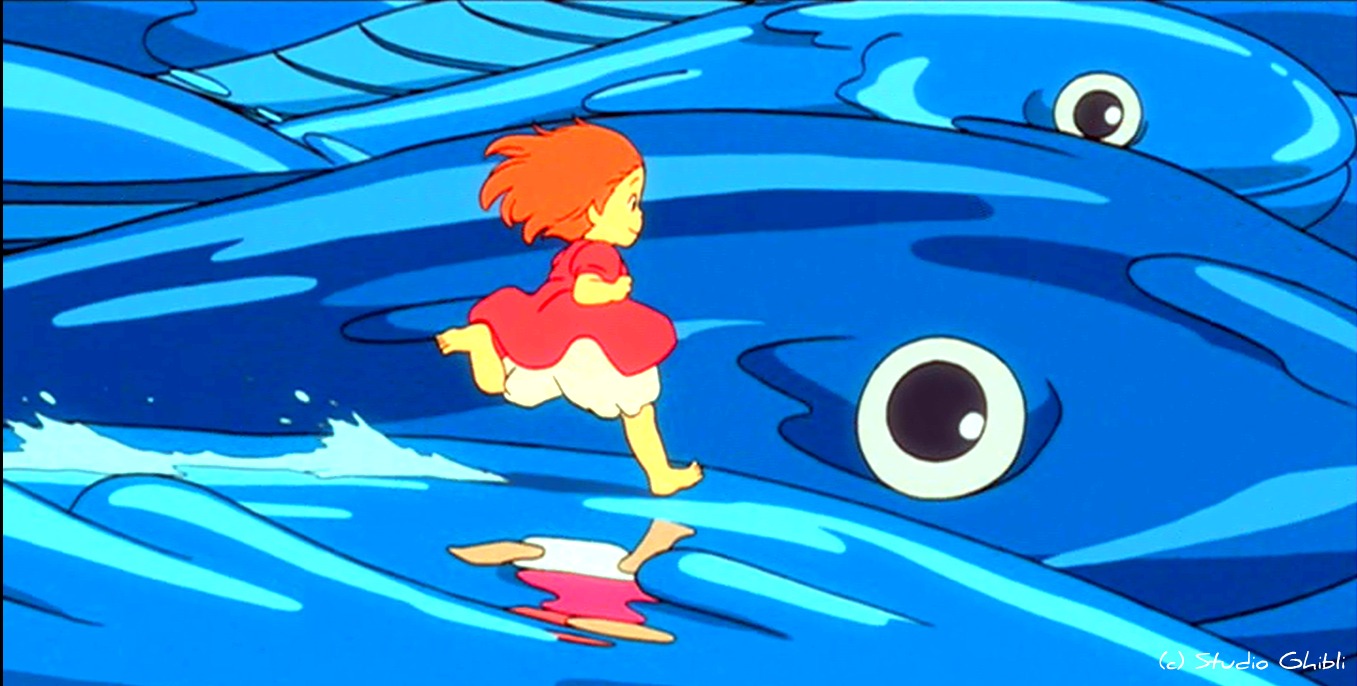

Miyazaki spends nearly fifteen minutes of screen time to deliver Ponyo’s message of defiance in the name of love: she literally moves the seas and pulls the moon out of orbit to accomplish her “want” – (try that move more in improv scenes: good audiences appreciate a physics refresher). From the start, Miyazaki makes clear: magic (1) isn’t easy, (2) takes time – and (3) isn’t always pretty. Ponyo grows her own damn legs – gradually and gawkily (as I call it, her “chicken-frog” state): with them, she runs diligently toward her goal, Sosuke – without regard for the fact that he’s across an ocean.

In sum: Ponyo runs on waves in the middle of a tsunami – that she is causing – because she is f**king going to become a girl and get to Sosuke. (Caveat: it takes a little help from family and friends – in Ponyo’s case, dad’s magic potions and support from her “community,” the ocean.) Calling it: the climax of this sequence is the most cathartic hug in cinematic history – WAY more satisfying than The Notebook.

Checking-in to compare with Ariel, real quick: this is what Ponyo does in lieu of singing a song about being part of a different world. Ponyo’s “I Wish” number not only states its want, it accomplishes it – and I believe girls of all ages are better off seeing more storylines like it.

ALSO: Ponyo meets her goal within the first, like, half hour of the movie…

Ghibli Girls tend to be overachievers (I love that about them). Miyazaki’s films frequently dare to give a girl a “want” early, then let the consequences breathe – all the while keeping their young protagonists in the driver’s seat. This structure provides kids with roadmaps for how to handle adventures other side of the unknown – the side they probably didn’t consider: hugging the boy in a storm is nice, but what comes next? Reminder: there’s been a tsunami – one Ponyo caused as a consequence of going after what she wanted at full-speed. Hard choices and sacrifices lie ahead – in fact, consequences and lessons will be Ponyo’s climax (not an epic embrace between the two main characters).

The bulk of Ponyo’s plot takes place after Ariel’s end credits have rolled…

While Sosuke lives and learns, Ponyo undergoes a metamorphosis. She learns the limits of her power and makes her first real decision: (to paraphrase Dan Savage) choosing her logical family over her biological one. Perhaps my favorite lesson from Ponyo, which Sosuke demonstrates repeatedly (and Ponyo discovers for herself): magic isn’t required to step-up and do the work.

Growing up as a girl is hard enough, all by itself. Ursula may be a cool villain – she gets the most interesting musical number in Disney’s version – but she’s not necessary to tell a compelling story about a girl who figures out she’s different from her parents and needs to rise up inside a community that doesn’t “get” her. As Eighth Grade proves: there’s a story in that alone. (Ponyo’s “chicken-frog” state might as well be eighth grade: it’s super-awkward; she doesn’t comprehend – nor can she control— any of her power; and ABSOLUTELY EVERYONE near her is affected by it.)

Ponyo explores a happiness that stems from the soul and has nothing to do with being a Princess: sometimes a girl just wants to hug her friend and eat some ham. And some loves are worth the waves.

P.S. It’s still early in the life of JMSunderduress, so let me continue to set expectations: in my last two posts I’ve opened gateways into sumo and Studio Ghibli – both of which, of course, come from Japanese culture. Not all blog entries will live in this lane. (Oddly enough, the top two directors on my recent watch list are Hiyao Miyazaki…and Paul Verhoeven. My taste in cinematic feminism runs the spectrum – and, yes, an article about Showgirls is swimming around my brain: NOT NEARLY ENOUGH DANCING. I HAVE NOTES.

TURN TO THE NEXT GHIBLI GIRL ADVENTURE…

And some more JMSunderduress you may enjoy:

BOW. REFLECT. GO AGAIN TOMORROW. (sumo)

RODGERS & HAMMERSTEIN’S CAROUSEL: IF I REWROTE YOU

SHINY AND OH SO BRIGHT (The Smashing Pumpkins + personal coming-of-age nostalgia)