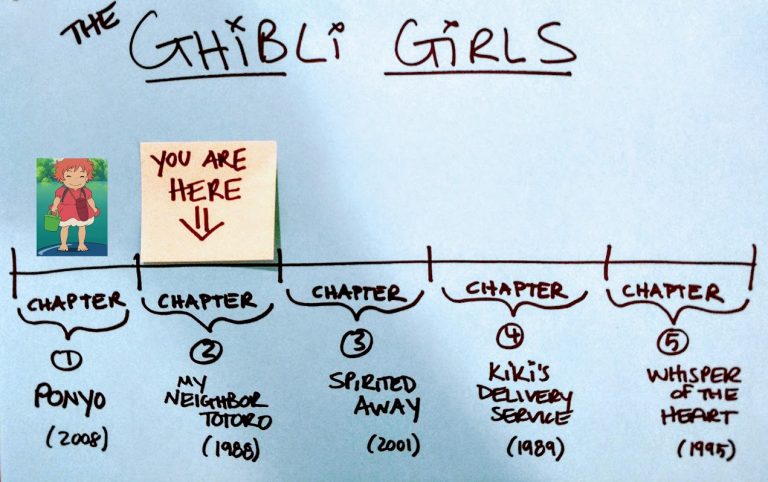

(This chapter assumes familiarity with THE GHIBLI GIRLS to this point.)

COME WHAT MEI:

FACING FEARS WITH WARM BELLIES

AND WELL-INTENTIONED CORN

My Neighbor Totoro

Released: 1988

Protagonist Age: 4

Appropriate Viewing for: ALL AGES (*worth noting: not all Ghiblis are*)

Miyazaki’s Role: writer/director

Inspiration: Miyazaki’s fascinating brain in the mid-70s, while he worked on the staff of a TV series (Isao Takahata’s 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother) –

TV writing occupied nearly all of Miyazaki’s time and perpetuated a hectic and hurried lifestyle he didn’t enjoy. Miyazaki felt surrounded by, and working in service of, an entertainment culture fixated on guns, action and speed. He imagined a movie – and subsequently an entire animation studio – that could succeed using an entirely different approach that, instead, promoted tranquility and innocence.

Miyazaki dared to focus years of his life developing and pitching storyboards of a young girl – no special powers, no past trauma to overcome, just a girl – befriending magical forest-dwelling monsters called “Totoro” (name based loosely on Tokorozawa, a town where Miyazaki had lived).

We are all better for it:

Here is a children’s film made for the world we should live in, rather than the one we occupy. A film with no villains. No fight scenes. No evil adults. No fighting between the two kids. No scary monsters. No darkness before the dawn. A world that is benign. A world where if you meet a strange towering creature in the forest, you curl up on its tummy and have a nap.

-Roger Ebert, in his four-star review of My Neighbor Totoro

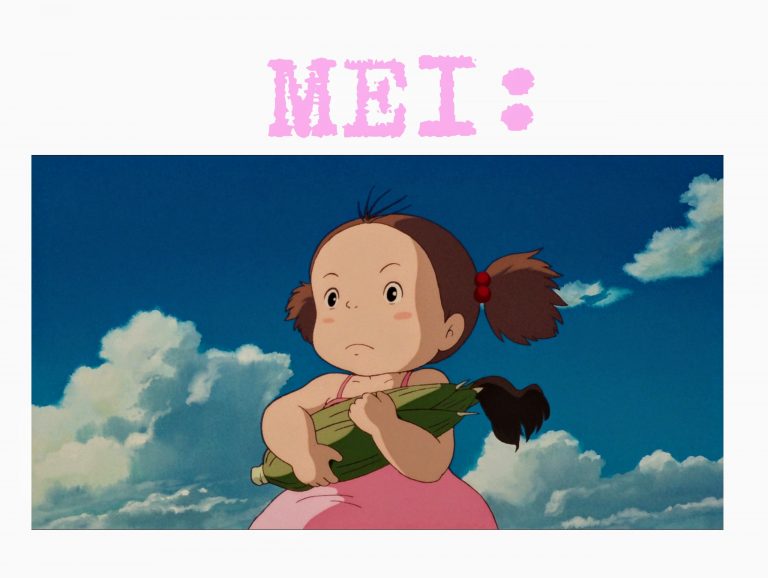

If Ponyo symbolizes self-identity and soul-driven love, Mei serves as a beacon for trust and leaning – literally – into the unknown.

Unlike Ponyo, Mei doesn’t come from magical lineage: her parents aren’t Mother Earth and a sea sorcerer, simply a professor and [temporary] hospital patient. Also unlike Ponyo, Mei is happy with the world she’s in and the family she’s got: she isn’t looking for a new life, she’s merely looking to better understand the one she’s living.

My Neighbor Totoro contains a simple setup: Mei, her big sister Satsuke, and their dad (the Kusakabes) are moving to the country (Matsugo, approximately 20 miles northwest of Tokyo – where Dad teaches). They move into a big, old, “haunted” house looked after by their new neighbor, Nanny, who works in a nearby rice paddy; Nanny’s grandson, Kanta – Satsuke’s age, maybe 7 – is Kayla Day-level awkward, particularly when faced with the opposite gender. The end of the schoolyear approaches: Satsuke and Kanta attend, Mei’s not quite old enough – which leaves her free to explore the forest and its creatures. Because it’s rural Japan in the 80s, there are no screens or social media apps; no school-wide pool party to dread: Mei and Satsuke play outdoors in the gorgeous bucolic backdrops that drench Ghibli Girl worlds.

But life, though picturesque, is far from perfect: the Kusakabes’ new home appears to contain a rotting foundation; Mom is sick in the hospital; sometimes Dad forgets his umbrella and misses his bus home from work – or oversleeps and forgets to pack school lunches – or naps and doesn’t notice his four-year-old daughter wandering off into a forest. These are real people with real problems – who happen to be stunning cartoons.

From the start, Miyazaki shows that the girls do feel fear when confronted by the unknown – they simply push through scary moments:

![]()

Dad teaches Mei and Satsuke that laughter helps bring light to any dark place – which leads the sisters to laugh, roar and cartwheel in the faces of “soot sprites” they unearth. Nanny adds that if the soot sprites deem new tenants “nice,” they bring no harm and will move out – which happens soon thereafter. (Nanny too acknowledges that children and adults see the world differently: she can no longer see soot sprites at all.)

(Soot sprites referenced multiples times here for two reasons: (1) fun to say (try it!); but also (2) they will come up again in Spirited Away/next chapter of The Ghibli Girls.)

Basically, the opening of My Neighbor Totoro lays out solid tips for any new life experience: chase curiosity, laugh your way through fear, respect different points of view – and don’t be a dick.

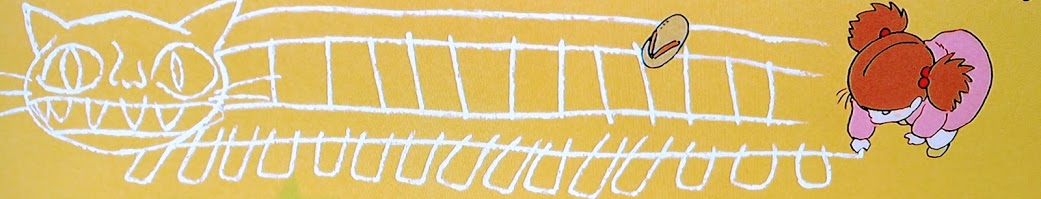

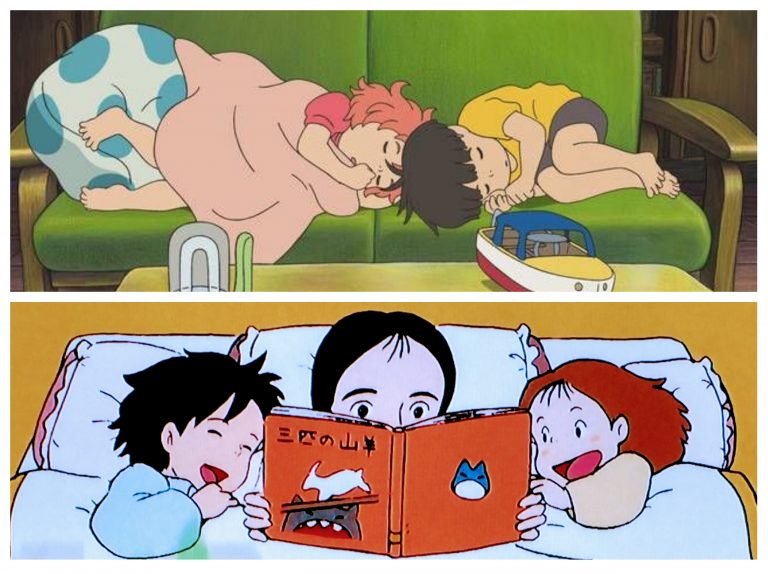

Like Ponyo, Mei is eager to explore: her first unsanctioned solo adventure leads deep into the roots of a large camphor tree on the family’s property, where she lands softly on the belly of a sleeping Totoro. Much like Sosuke discovering Ponyo, Mei reacts to Totoro as something she understands immediately, on instinct. Shortly after meeting, the two fall [back] asleep together.

Audiences meet Totoro through Mei’s eyes – a lovely gift from Miyazaki. Mei’s first interaction with Totoro reminds us all how it feels to love like a four-year-old, showing what humans crave on a most primitive level: a safe, warm place to surrender to sleep.

Let’s be real: at any age, there are few better ways to conclude an adventure than napping on a soft belly. …Come to think of it, here’s a quick, off-the-top-of-my-head list of five things Totoro provides Mei and Satsuke: (1) top-notch sleeping accommodations; (2) feelings of safety in a new village; (3) instrumental lullabies; (4) gardening assistance; (5) an enchanted ride, wherever and whenever needed – even if the destination is a person. As an adult clocking Totoro’s actions, I cannot help but call out: these are all awesome qualities in any partner. No big surprise, I suppose, that Hayao Miyazaki would choose Totoro as the mascot for Studio Ghibli – the equivalent of Pixar’s desk lamp (only way cuter):

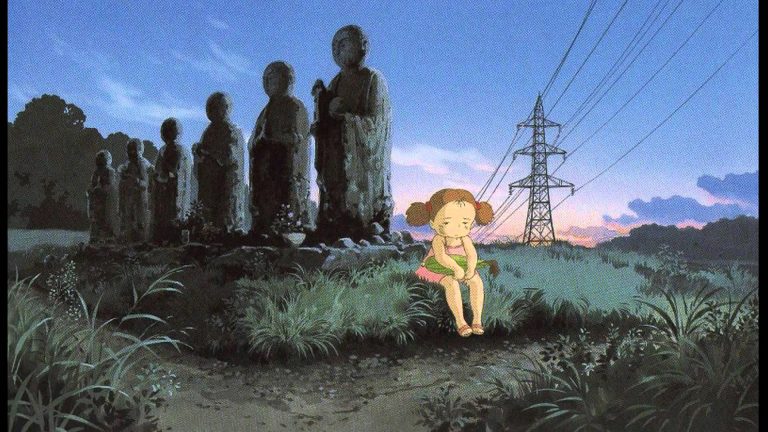

Like Ponyo, Mei accomplishes her initial “want’ [exploring/settling into her new village] fast. So, again: lots of time for lessons and consequences. In Mei’s case, lessons and consequences play out largely during a subsequent solo quest to deliver an ear of corn to Mom in the hospital: she may not have magical powers, but Nanny teaches Mei that the corn is vitamin-rich, and vitamins will help Mom get better. In four-year-old logic, an immediate expedition to the hospital is in order (Mom needs corn, duh) —during which Mei gets lost.

This second (mis-)adventure takes the time to show some more realistic consequences of heart-following. Mei’s objective has nothing to do with romantic love – she simply wants her mom to heal and come home. But in the wake of her poorly-planned quest, family and community need to drop what they’re doing to chase down the dreamer: days and schedules are offset. Loved ones worry. Besides, such outings are best accomplished in-tandem with a group: Frodo had his Fellowship; Ocean had his Eleven (and his twelve, and his thirteen…and now her eight); Nic Cage had his plane cabin of dangerous convicts – Hell, even Totoro rolls with a crew:

Magic is by no means Mei’s only source for learning about teamwork: she receives near-daily lessons in human limitation and adaptability from her consistently imperfect dad. Mr. Kusakabe is, at all times, open with his daughters about his shortcomings: he isn’t a superhero and never pretends to be. A helpful consequence of this attitude: Mei doesn’t freeze immediately when confronted with a flaw in her own plans – or lack thereof. She doesn’t expect to sprout wings and fly herself…but also doesn’t close herself off from the possibility of Totoros and cat buses.

Miyazaki’s influence exists in a sphere significantly larger than his following, and the ripples created by his work are wonderful (i.e. Pixar’s admitted Ghibli influence; my context-free, instinct-based love of the photo above…). I believe a generation of girls raised with more direct influence from Ghibli heroines better arms them for adolescence, as though covering an Achilles heel American movies aimed at the same demographic tend to leave unprotected.

There exists a certain fatalism in most American films for little girls: wandering off alone into the woods or walking down a strange basement staircase never ends well. (Suffice it to say: there will be no rescue-by-cat-bus.) American girls learn to be afraid of the world from a young age…and stay that way. Little time for magic, if any. A miracle of Miyazaki movies: their ability to explore the world of little girls without ever appearing creepy. Ghibli Girls provide examples of curious girls who off-road and adapt, always using whatever’s in the tank – but never punishing themselves for anything lacking.

Ponyo understands magic from the inside; Mei experiences it outside-in. Between these two Ghibli Girls, Miyazaki presents a variety of perspectives on how to live a life touched by magic while facing fears and unknowns.

But magic, of course, isn’t everything: at the end of the day, it all comes down to where a girl can sleep the soundest.

P.S. A reminder to all creatives: it took Miyazaki several years of persistence fueled by strong self-belief to turn My Neighbor Totoro [and Studio Ghibli] from one man’s dreams into a world’s reality.

…But THIS was on the other side of Miyazaki’s “want” – and (again) we are all better for it. (Keep drawing your Totoros.)