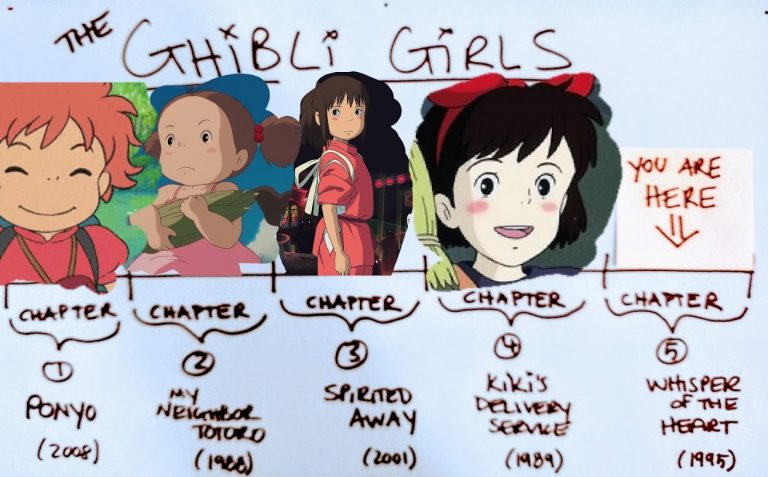

(This chapter assumes familiarity with THE GHIBLI GIRLS to this point.)

YOU HAVE EVERYTHING YOU NEED

Whisper of the Heart

Whisper of the Heart

Released: 1995

Protagonist Age: 14

Appropriate Viewing for: ALL AGES! (though perhaps less fun for young children)

Miyazaki’s Role: writer (directed by Yoshifumi Kondō)

Inspiration: adaptation of 1989 manga by Aoi Hiiragi, same name.

Whisper of the Heart was to be a “changing of the guard” at Ghibli, passing the torch carried by Miyazaki (and Isao Takahata) to rising star animator Yoshifumi Kondō: tragically, this was the only film Kondō directed before his untimely passing in 1998 – at age 47. Ironically, many attribute his death to excess stress brought on by the increased responsibility at Ghibli: after all, Miyazaki had created entire worlds from his mind – which Kondō attempted to upload to his own, and go about life as-normal. The experiment failed.

A cautionary tale perhaps, maybe even a conspiracy theory, but I find it curious that an artist who spent years of his life developing such inspiring protagonists somehow missed their lessons. I mention this bit of Ghibli history because I believe it to be a crucial reminder – especially to creatives – that it is impossible to climb inside anyone else’s genius. Mentors can be wonderful, heroes can be helpful, but at the end of the day a mind can’t function fully on the fuel of someone else’s dreams.

For readers coming into this series already familiar with the Ghibli canon, Whisper of the Heart may seem an odd choice for a “finale”: a less popular film from the studio’s archive, loyal fans (myself included) gravitate toward its message of sticking to one’s own path – even when that path is confusing and its destination unknown.

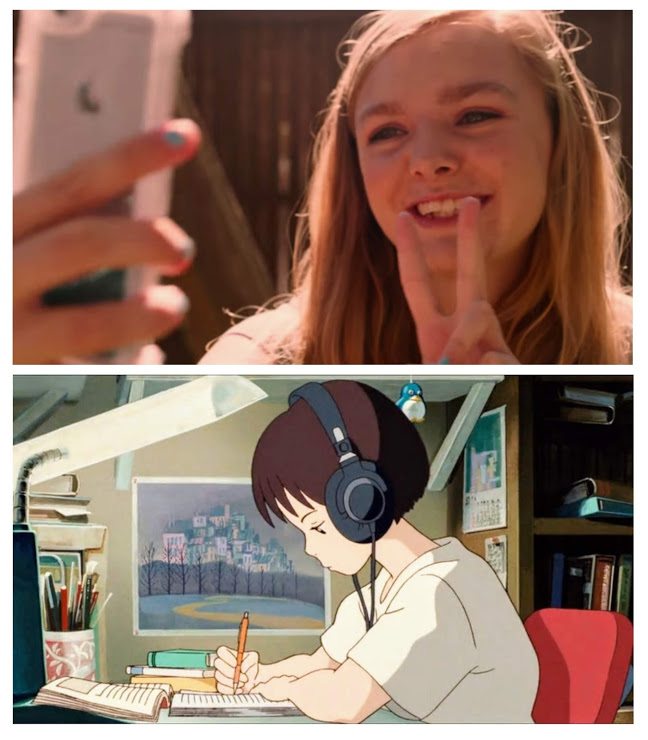

My intention at the start of this series (inspired by Bo Burnham’s Eighth Grade): promote a handful of lesser-known heroines in American culture alongside Kayla Day, to help future generations of girls find their way amidst social media-induced insecurity and self-doubt. Ghibli Girls are imperfect characters living in imperfect worlds that provide audiences of all ages portals back into childhood wonder.

Fittingly, this final chapter covers Ghibli’s closest analog to Eighth Grade: we end back where we began.

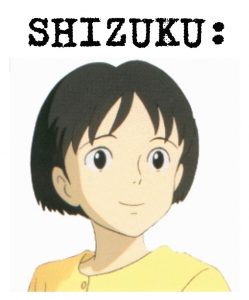

Shizuku Tsukishima, like Kayla Day, is a non-magical girl in a non-magical world, finishing out middle school amidst an adolescent minefield of boys, societal expectations, and artistic inspiration. Both girls cope using the filters of their own unique, if inelegant creative endeavors: two raw, unpolished female protags learning about life through their raw, unpolished art. Kayla has a YouTube channel; Shizuku writes fantasy stories and parody songs (including a city-girl anthem I’ve come to sing to myself while walking home from the subway at night, “Take Me Home, Concrete Roads”).

Shizuku Tsukishima, like Kayla Day, is a non-magical girl in a non-magical world, finishing out middle school amidst an adolescent minefield of boys, societal expectations, and artistic inspiration. Both girls cope using the filters of their own unique, if inelegant creative endeavors: two raw, unpolished female protags learning about life through their raw, unpolished art. Kayla has a YouTube channel; Shizuku writes fantasy stories and parody songs (including a city-girl anthem I’ve come to sing to myself while walking home from the subway at night, “Take Me Home, Concrete Roads”).

Shizuku’s Ghibli Girl “want”: to be a writer. (Shizuku’s Ghibli Girl adventure of “lessons & consequences”: what the life of a writer really looks like.)

When the story begins, Shizuku’s writing already, translating lyrics for her classmates’ graduation: she’s already “doing the thing” and being recognized, positively, for it. Seems innocent enough. This time, however, our Ghibli Girl must navigate her “want” amidst middle school madness – which means all bets are off.

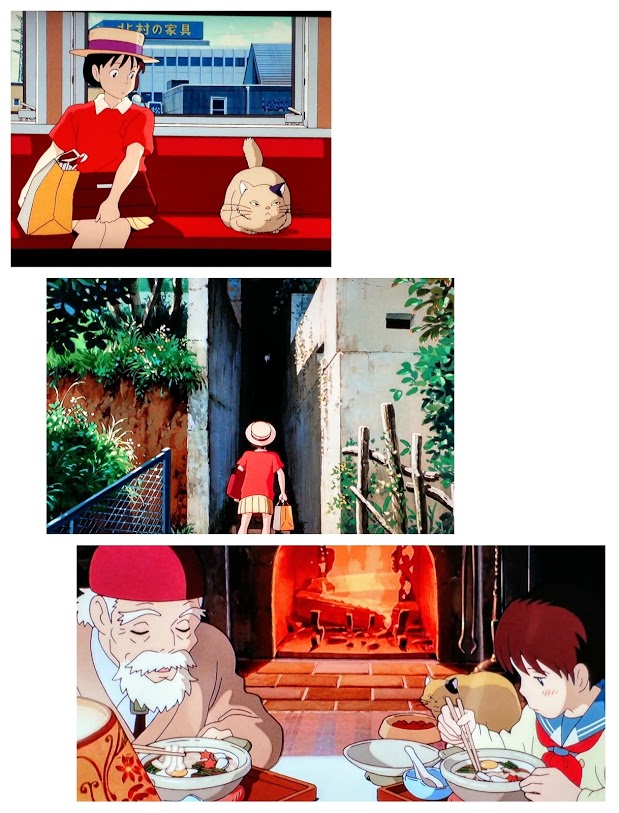

Though grounded in the reality of present-day Tokyo, traces of magic surround Shizuku: artifacts from a childhood she’s outgrown but continues to channel (with help from Ghibli artists and animators).

In Shizuku’s writing, coincidentally, artisans are the descendants of magicians: she envisions a world where creatives are related to, and touched by, magic. Pleasantly, Whisper of the Heart is full of callbacks to enchantments explored by other Ghibli Girls, some less subtle than others: board another train (this time, to the library – not a witch’s cottage), enter another dark tunnel (this time, leading to an antique shop – not a bridge to the spirit world); trust more cats (here, merely fur and figurine – a cat does take the train, but not through any magic, he is just lazy). We even find another moment of comfort in big bowls of steaming ramen.

In these trying teenage times, we are always but one association away from a familiar memory of Ghibli magic:

Because we are (still) very much in a Ghibli Girl world, agency has no “minimum age.” This makes Shizuku free to express a want at any time, and pursue it using any resources at her disposal – armed with the knowledge that adventures carry consequences. Ponyo ran on magical waves for Sosuke; Mei rode a Cat Bus for Mom; Chihiro hopped a Spirit Train for Haku; Kiki hopped on mom’s broom for herself – and now Shizuku steps into her imagination, ready to share herself with others.

Because we are (still) very much in a Ghibli Girl world, agency has no “minimum age.” This makes Shizuku free to express a want at any time, and pursue it using any resources at her disposal – armed with the knowledge that adventures carry consequences. Ponyo ran on magical waves for Sosuke; Mei rode a Cat Bus for Mom; Chihiro hopped a Spirit Train for Haku; Kiki hopped on mom’s broom for herself – and now Shizuku steps into her imagination, ready to share herself with others.

For the purpose of concluding this series, there is one final Ghibli Girl lesson left to cover: romance.

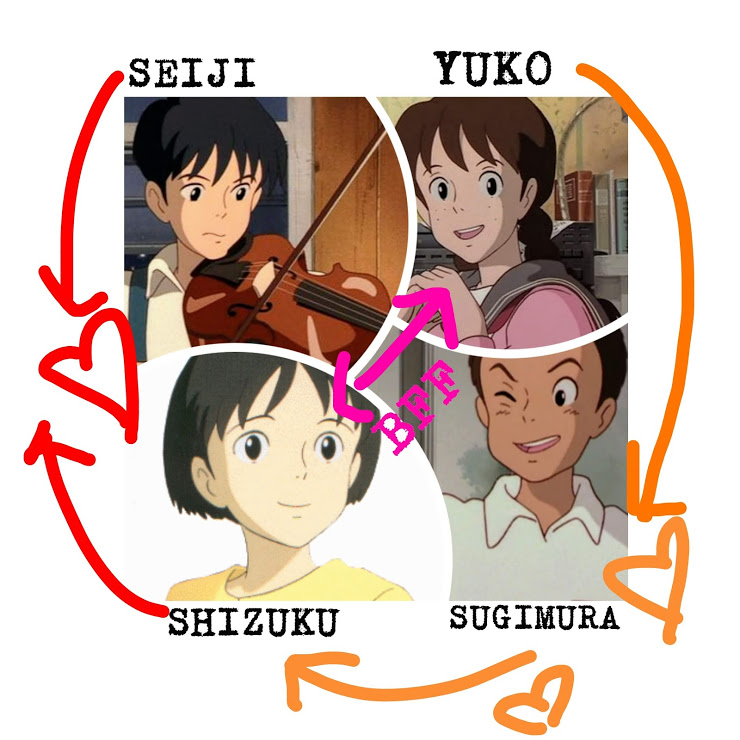

Shizuku’s BFF Yuko likes Sugimura. Sugimura likes Shizuku. Shizuku likes Seiji – who likes Shizuku, but mostly loves violin-making.

Shizuku’s BFF Yuko likes Sugimura. Sugimura likes Shizuku. Shizuku likes Seiji – who likes Shizuku, but mostly loves violin-making.

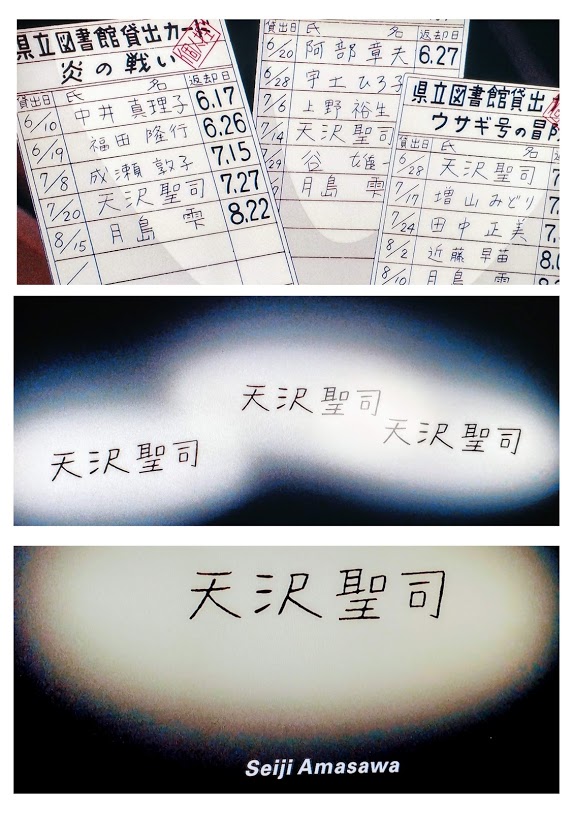

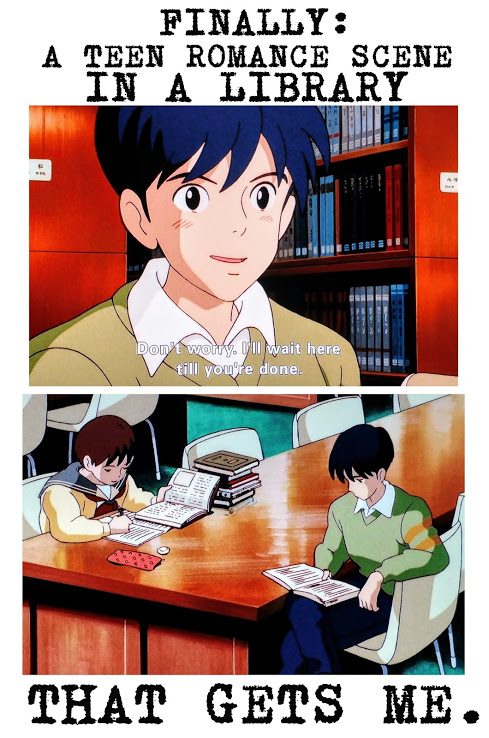

In a case of nerd-love at its finest, Shizuku first becomes aware of Seiji through their shared love of literature: his name appears on the checkout cards of nearly all 20 books she reads (for fun) over her summer vacation. Their relationship is, quite literally, “in the cards”:

A dedicated bookworm with an independent spirit, I like to think of Shizuku as Disney’s Belle – with less pretention. She finds solace in stories – and so, apparently, does a boy named “Seiji Amasawa.” (Sugimura and Yuko crush in a more traditional manner: he’s a big-mouthed bench-warmer on the baseball team; she frets about fashion and unwanted freckles.)

A dedicated bookworm with an independent spirit, I like to think of Shizuku as Disney’s Belle – with less pretention. She finds solace in stories – and so, apparently, does a boy named “Seiji Amasawa.” (Sugimura and Yuko crush in a more traditional manner: he’s a big-mouthed bench-warmer on the baseball team; she frets about fashion and unwanted freckles.)

Shizuku’s early in-person encounters with Seiji – before becoming aware of his identity – follow a pattern of playful banter based on observations of the other’s behavior and shared interests. They acknowledge one another as whole, imperfect, quirky people – simultaneously intriguing and irritating (about as good as anything ever feels in middle school). Cutting the co-ed clumsiness its deserved slack, their treatment of one another roots itself in a place of curiosity and care. It’s another, more nuanced, version of leaning into the unknown: we’re no longer four, lost in a forest, napping on Totoros.

The “unknown” in Whisper of the Heart unfolds early and unpredictably, when Shizuku walks down a flight of basement steps…

Now, in an American film this probably wouldn’t end well for Shizuku – she may not leave that basement alive. Basements get a bad rep both in life and on-screen: dirty deeds, buried bodies, secret alligator pits…

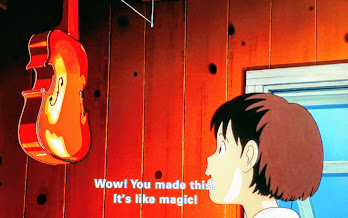

…but sometimes there’s no serial killer, no shark tank, just a boy making violins (in a “basement” with a surprise city skyline – because it’s built into a cliffside, another example of Ghibli gorgeousness). Any Midwest-raised kid can vouch: basements can be scary, sure, but they can also be places of creative expression and vulnerable joy – places where magic appears in something real.

Places where awkward humans come to collaborate, maybe through music.

…And even when the next unknown comes down the basement stairs, moments later:

(In an American film this definitely feels like it wouldn’t end well. I don’t even want to know what the guy in the glasses would do in an Eli Roth film…)

But everything’s OK – AWESOME, even! Turns out it’s just a band coming to play back-up.

Ghibli Girl Lesson: sometimes the scary unknown is there to support – so SING OUT.

(Bonus for those watching in Japanese: when the jam session ends, Seiji’s grandfather introduces his “musical friends.” – That’s it: “These are my musical friends.” That’s all we need to know – and it’s perfect. Now that’s a Michigan basement.)

So, instead of being trapped in the well, putting the lotion in the basket, we begin the relationship of Shizuku and Seiji on a summer night scored by the music of John Denver.

On the other side of Ghibli Girl childhood, it is time to incorporate the “wants” of partners: Seiji wants to study violin-making in Cremona, Italy. When he tells Shizuku about an upcoming two-month trial apprenticeship abroad, she decides to use the time to write a novel. At no point is this presented as an either/or: the boy or her dream. No one considers dropping “their” thing. This isn’t a time for sacrifice, but for support during a period of exploration.

There is a mutual respect for the “want” of the other – even on Seiji’s last night in Tokyo, pre-departure:

While Seiji trains in Italy, the film presents a realistic portrait of Shizuku’s schedule as an aspiring writer. Like Kiki’s coming-of-age, Shizuku must overcome obstacles largely on her own: Mom’s in summer school, busy finishing her Master’s degree; Dad’s a librarian who works long hours; big sis Shiho is on the verge of moving out of the family home, into her own place. (An entire scene takes place between Mom and big sis Shiho, discussing their upcoming professional plans and financial situations – no talk of Shizuku whatsoever.)

While Seiji trains in Italy, the film presents a realistic portrait of Shizuku’s schedule as an aspiring writer. Like Kiki’s coming-of-age, Shizuku must overcome obstacles largely on her own: Mom’s in summer school, busy finishing her Master’s degree; Dad’s a librarian who works long hours; big sis Shiho is on the verge of moving out of the family home, into her own place. (An entire scene takes place between Mom and big sis Shiho, discussing their upcoming professional plans and financial situations – no talk of Shizuku whatsoever.)

Every character walks their own path, at their own pace. Not everyone needs to write a novel or build violins abroad at fourteen (although that’s acceptable, too). Other students stress about more traditional issues, like school – so does Shizuku’s mom, for that matter. In a confrontation regarding her declining grades, Shizuku’s father drops some supportive wisdom, telling his daughter, “not everyone has to be the same.” (Followed shortly thereafter by an equally wise warning: “it’s not easy when you walk your own road.”) Though they may not understand it fully, Shizuku’s parents encourage her work: they’ve got their lives, she has hers.

Chasing down a feeling and preserving it on paper is gutsy stuff at any age, and creative work takes its toll on a human body. (Remember, Ghibli Girl: “wants” have consequences – now go listen to “Finishing the Hat.”)

Shizuku’s day-to-day life may feel familiar – especially to those of us who share her calling:

Up writing until 4AM. Forgetting to eat, change clothes, or keep appointments; lost in the world created on-the-page. Occasionally crying while eating chips, for no apparent reason. Equally on-point: Shizuku’s inner-monologues, drenched in self-sabotage and doubt, never satisfied with her creative work.

Up writing until 4AM. Forgetting to eat, change clothes, or keep appointments; lost in the world created on-the-page. Occasionally crying while eating chips, for no apparent reason. Equally on-point: Shizuku’s inner-monologues, drenched in self-sabotage and doubt, never satisfied with her creative work.

Her imagination, however, is another matter entirely.

Her imagination, however, is another matter entirely.

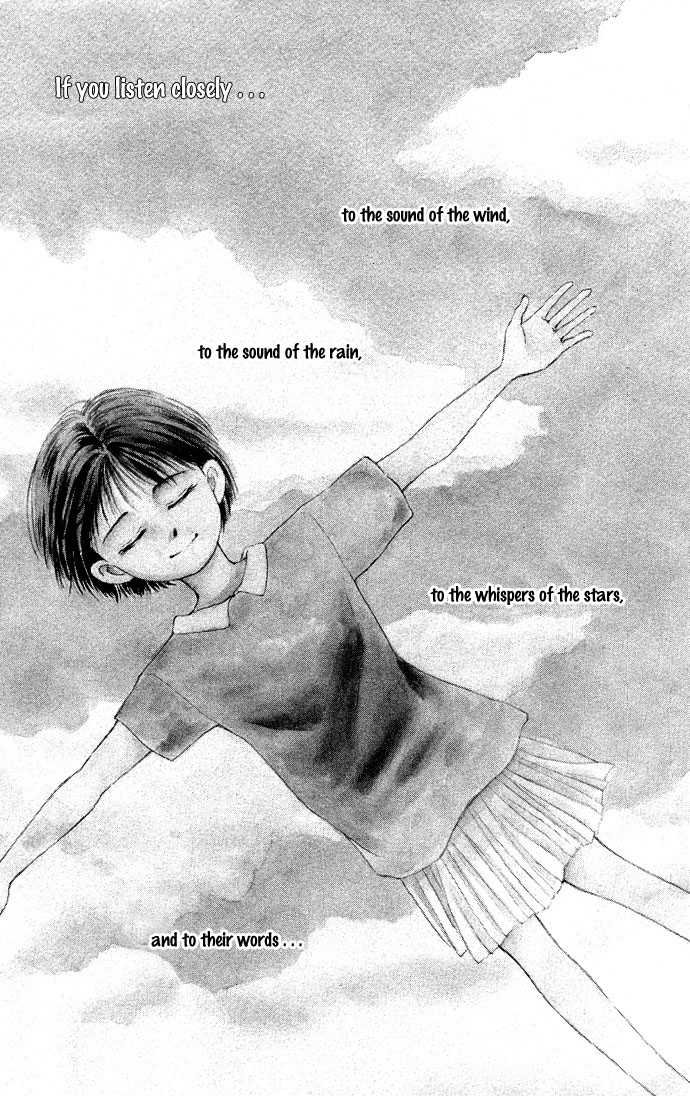

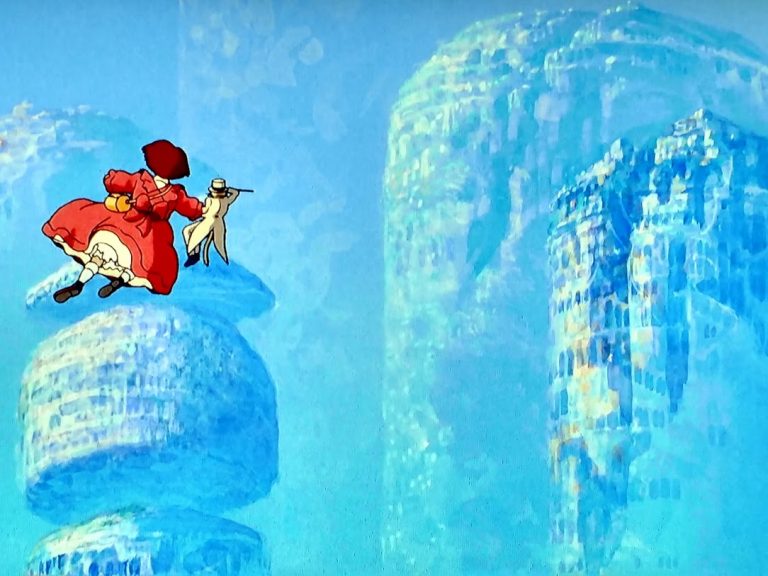

Accompanied by talking cat guide “The Baron” (inspired by an antique store figurine), Shizuku embraces her creativity full-on and flies through the magical worlds in her mind. (Count on it: anytime Miyazki is involved, the film will find a way to incorporate flight.) But Whisper of the Heart grounds its fantasy in reality, reminding audiences of the constant opportunities available to channel childhood creativity and harness its power to tackle adult goals (like a finished manuscript) –

– and adult relationships.

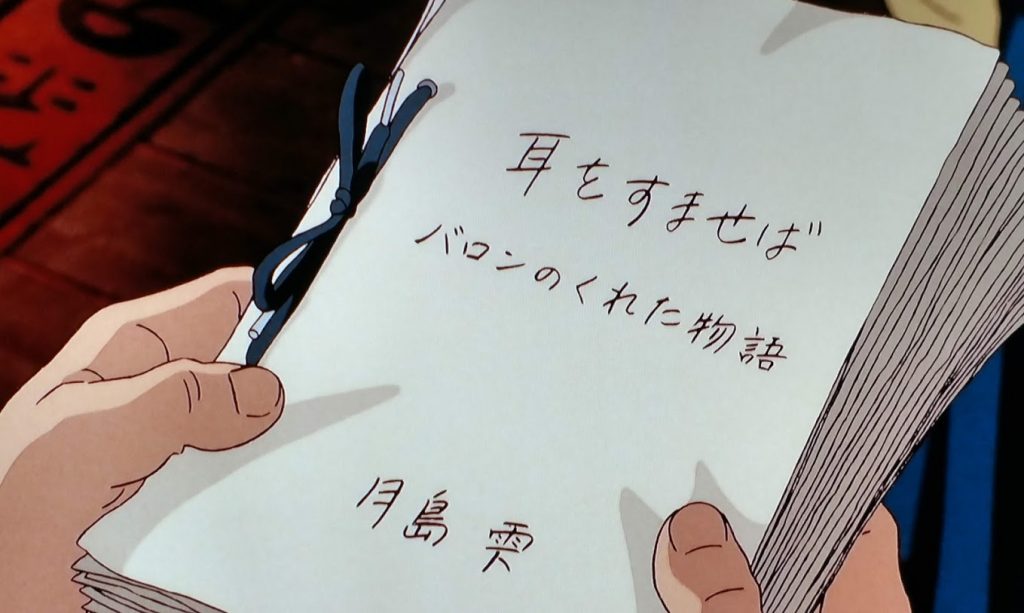

Magic comes from hard work; greatness requires patience and time. Shizuku and Seiji take risks and follow dreams – though neither proves a prodigy at their respective craft: Shizuku’s first draft is raw and will require heavy editing; Seiji has decades more training ahead to achieve greatness in violin-making. And Seiji’s romantic homecoming gesture ends not in magical flight, but a literal uphill climb for both parties – a sweaty one at that.

Magic comes from hard work; greatness requires patience and time. Shizuku and Seiji take risks and follow dreams – though neither proves a prodigy at their respective craft: Shizuku’s first draft is raw and will require heavy editing; Seiji has decades more training ahead to achieve greatness in violin-making. And Seiji’s romantic homecoming gesture ends not in magical flight, but a literal uphill climb for both parties – a sweaty one at that.

A note on the film’s final 30 seconds – which I am going to spoil because, on its surface, it may otherwise strike as a confusing place for this series to end:

(I’ve watched all five of these films in their original Japanese as well as their English dub; in every case, I prefer the Japanese. Whisper of the Heart’s translated final lines, however, change the ending in a way that softens its landing for American audiences – and merits a mention.)

On the sunrise of his return, Seiji asks Shizuku if she “could see [them] getting married someday.” (This is the English dub – the original Japanese is a straight-up marriage proposal.) Seiji assures Shizuku that he will be a professional violin maker, she can be a professional writer – and he concludes by asking if the idea sounds “corny.” Her response, in the English dub: “it’s a little corny – but you’re a violin maker, not a writer.” (The original Japanese is a direct acceptance of the proposal.) To end on a sudden engagement between two fourteen-year-olds is jarring, I think, for most American audiences – especially as conclusion to a film with a strong, independent female lead. So, heads up for those who, like me, generally prefer the original Japanese: its ending may disarm – and disappoint. (If this happens, I suggest rewinding to the “musical friends” scene and re-watching that as an encore – repeat as many times as desired; it’s wonderful.)

As written, I suppose we simply find our way back to a more traditional Disney Princess ending: a presumed happily ever after, achieved via marriage.

As it happens, there is a “princess” in Whisper of the Heart – though she appears only briefly: a figurine in an antique grandfather clock, who spends most of her time in sheep form. This unnamed princess is lives trapped in the clock’s face: only when the clock strikes twelve does she appear a princess – which is the only time her love, the king of dwarfs, comes to look at her. This magical, romantic life she leads is, at bottom, a sad one.

Come to think of it: all of the passion-based love stories in Whisper of the Heart come tinged with sadness – lovers separated by time, space, magical curses. More functional pairings – Shizuku’s mom and dad, for example – are neither passionate nor tragic: they simply coexist. No fireworks; no fires. Refreshingly, they’re never judged harshly for a lack of desire. Ghibli Girl films treat passion as a sub-genre of adventure, no better or worse than any other.

And that’s the finish line, really: to view romantic love simply as one possible adventure in life – but by no means the only one, and not even a necessary one. There are many roads to travel, a variety of adventures along the way, all worth taking (or, at very least, considering) – all of which come with their own tailor-made consequences.

Write your own story. Find your musical friends. You have everything you need.

EPILOGUE

I am thrilled to hear from readers who have (re)explored Studio Ghibli films since the start of this series: thank you for taking the time to share your stories – please feel welcome to keep them coming.

Bo Burnham’s Eighth Grade captured with cringe-inducing precision a life chapter that comes, for many of us, at the twin peaks of awkwardness and uncertainty. (Perhaps the only thing most eighth graders know for certain is their extreme levels of awkward.) Post-viewing/subsequent self-reflection, it led me down a research rabbit hole into the most common role models for girls that age – and left me desperate to help deepen the “coming-of-age” bench.

What I think the Ghibli Girls contribute: mascots for mental health, promoting habits of self-care. There is an unspoken awareness of mental strain in Ghibli films, paired with moments of “ma” that pause the magic and give our protagonists time to stop and eat some noodles, take a bath, lie on the grass and listen to dad’s radio.

So much of American childhood feels rushed, leaving less time to discover. But no matter an audience member’s age – or gender, going on a Ghibli Girl adventure carries with it the potential to revisit moments of childhood and make-up the lessons missed first time around.

I’ll end with a recent discovery of my own – which will no doubt reveal (more of) my connection to Whisper of the Heart:

Unlike Kayla Day, I didn’t have the Internet to reflect my experiences. Instead, I reflected – literally – via this Beatles mirror my mom handed down to me:

The mirror had hung in her childhood bedroom, witnessing chapters of her evolution – long before I entered the world. Decades later, (when I was right around Chihiro’s age), my parents helped me move and hang it across from my bed – where it caught the sort of moments Kayla Day recorded and posted on her YouTube channel. Lacking the technology for that kind of publicity, I sought self-confidence standing on a stage of my bed, positioning my head in the space between Paul McCartney and John Lennon, belting showtunes – including many Disney anthems. (And I’m willing to bet my mom did the same…)

My “musical friends,” The Beatles watched me prepare for each day of eighth grade – and the many chapters that followed, lucky to survive a number of moves I can no longer count. Currently, they reign over my keyboards – where they continue to judge my bedroom performances (and also remind me, helpfully, in moments of writer’s block, that lyrics can be as simple as “yeah, yeah, yeah” – or as silly as “I am the walrus / goo goo goo g’joob”).

Over the summer I started taking voice lessons (an early birthday present from my partner). Though I sang publicly throughout childhood, in choirs and musicals, my voice unconsciously lost volume during its years away from the stage – when my only “singing gigs” were funerals of loved ones. By the time I started The Second City’s Music Program, more than a decade later, I’d disconnected my singing voice from my diaphragm completely: some of my most clever improvised lyrics never made it past the first few rows. This unintentional softness affected my character choices: after all, we sing the way we see the world. I improvised long enough and frequently enough that it forced me to confront the “quiet” – because it made a statement about me as well, one I didn’t intend. (Suffice it to say, during my four years in Chicago I played a lot of vulnerable, low-status victims for a lot of aspiring comedians.)

Now nine lessons in, I have (re)learned how to amplify my voice – literally. In doing so, I cannot help but recognize that the amplification spills out into other areas of my life. (You are reading evidence of it.)

I now sing before many of my writing sessions: I find stretching out my vocal cords helps open up the voice I use on the page. (And, yes, Disney songs remain in the mix #HowFarIllGo #LetItGo.)

A related discovery: the more I study my voice, the more carefully I listen to the voices of others – which ultimately circles back to helping me better understand my own.

One final bit of Ghibli trivia: Whisper of the Heart’s Japanese title (耳をすませば / “mimi wo sumaseba”) translates literally to: “if you listen closely.”

If you listen closely: I cannot think of a more helpful coming-of-age mantra that answers how to unlock the magic in simple joys. Or how to empathize with a fellow soul – even if that soul is trapped inside a stink spirit.

BONUS: Meet Miyazaki’s “Musical Friends”

Joe Hisaishi is a delightful man, a gifted composer, and a friend/frequent collaborator of Miyazaki’s. (Though he did not work on Whisper of the Heart, his music underscored all four other Ghibli Girl films explored in this series.)

Please enjoy this clip of Hisaishi conducting an orchestra, several choirs — and one adorable little girl — as they join forces to celebrate the PONYO theme in 3-MINUTES OF GUARANTEED JOY:

More JMSunderduress you may enjoy…