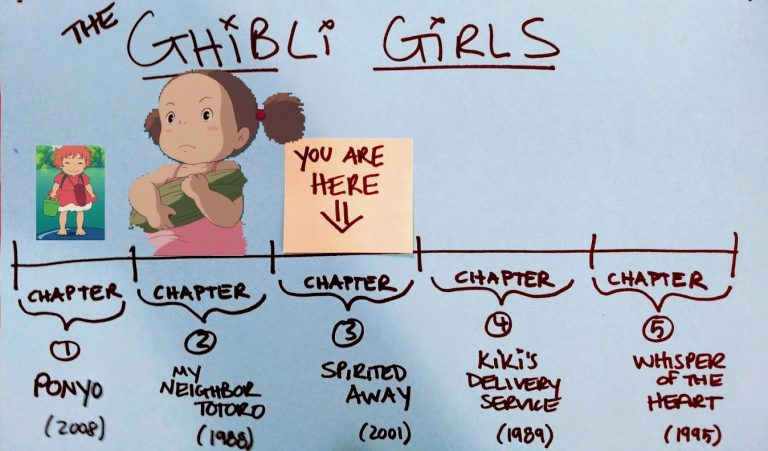

(This chapter assumes familiarity with THE GHIBLI GIRLS to this point.)

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Spirited Away

Released: 2001

Protagonist Age: 10

Appropriate Viewing for: *MOST* ages (PG: Miyazaki intended it for ten-year-old girls)

Miyazaki’s Role: writer/director

Inspiration: a friend of Miyazaki’s daughter, 10 at the time, joined for a vacation at the Miyazaki family mountain cabin: the girl’s sullen and apathetic nature fascinated Miyazaki – and a conversation with her inspired him to make Spirited Away. Miyazaki set out to make a movie in which such a girl finds herself endowed with agency, forced out of apathy, and empowered to work her way into heroine status. In doing so, he arguably made his masterpiece.

If you know one Ghibli film, it’s probably Spirited Away – the only foreign film to win an Oscar for Best Animated Picture. It presents a coming-of-age story about a moment in a girl’s life when change extinguishes naïveté, boundaries blur, and parents become incapable of answers or protection. Of Miyazaki’s eleven films, it provides an intersection of his coming-of-age stories and war epics.

To recap and expand upon Ghibli Girl themes: Ponyo teaches self-identity and soul-driven love; Mei’s lesson is trust, leaning into the unknown to discover magic; Chihiro faces fears and lets magic help activate her own [non-magical] power.

Some departures from previous Ghibli Girl trends: (1) Chihiro’s “goal,” unlike Ponyo’s or Mei’s, takes the whole movie to accomplish; (2) Chihiro must deal with lessons and consequences stemming not only from her own actions, but also the actions of others — including her parents; (3) she doesn’t get a consistent sidekick.

Spirited Away was my gateway into Ghibli films. I watched it first at home, alone, the night before Easter. I was recovering from a dance rehearsal: ice pack belt around my pelvis, foam roller detangling knots in my calves. (The glamorous life of an arthritic dancer in her mid-30s.)

I’d been meaning to try Miyazaki for months: a free viewing of Laika Studio’s Kubo and the Two Strings had recently blown my mind, and my film-loving friends were quick to point out: “it’s an American attempt at a Ghibli.”

What was “a Ghibli”? I didn’t know. (A consequence of full schedules: I have many cinematic blind spots — I’m finally beginning to address them.)

– My partner knew, however: he owned several, and on April 15, 2017, I learned. Here are some of the texts I sent him from that journey:

WHY IS EVERYTHING I’M AFRAID OF IN THIS MOVIE?

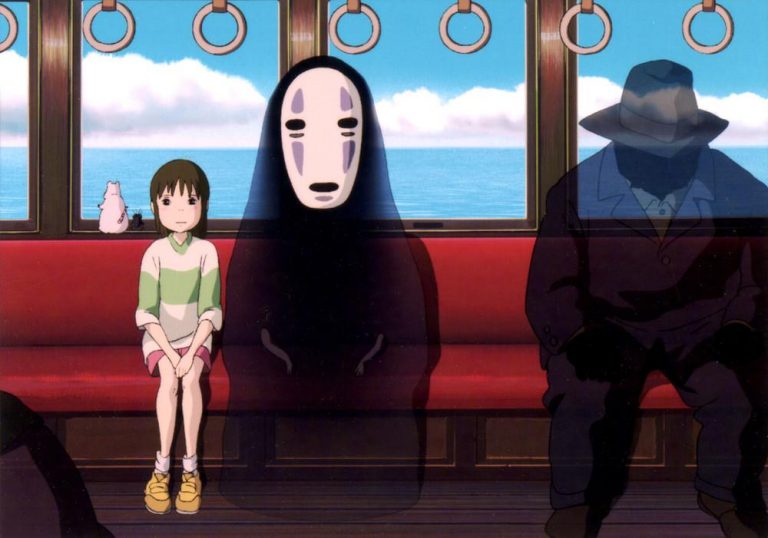

SPIRIT TRAIN: HOW DOES HE KNOW THE INSIDE OF MY SOUL?

ZENIBA’S COTTAGE FEELS LIKE MY GRANDMA’S HOUSE…HOW DOES HE DO THIS?

YUBABA REMINDS ME OF NORMA DESMOND

THAT WAS NOT WHAT I EXPECTED

…It was like nothing I’d ever seen before. I was confused by it, but knew I loved it and wanted more.

Recently I revisited Spirited Away with my parents, while visiting home. My mom slept through half of it (standard), and my dad called it “Polar Express meets Wizard of Oz by a guy on LSD who made great animation.” (He’s not wrong: there is a magical train, and there are sister witches [Zeniba and Yubaba – one with a trio of bouncing heads in lieu of flying monkeys]. Not sure about any LSD, but the animation is other-worldly.)

Trends I’ve noticed among those I’ve introduced to Ghibli thus far: questions; confusion; comments that the pacing feels different – something Miyazaki attributes to “ma,” a concept in Japanese culture often explained as the moment between two claps – emptiness – breathing space.

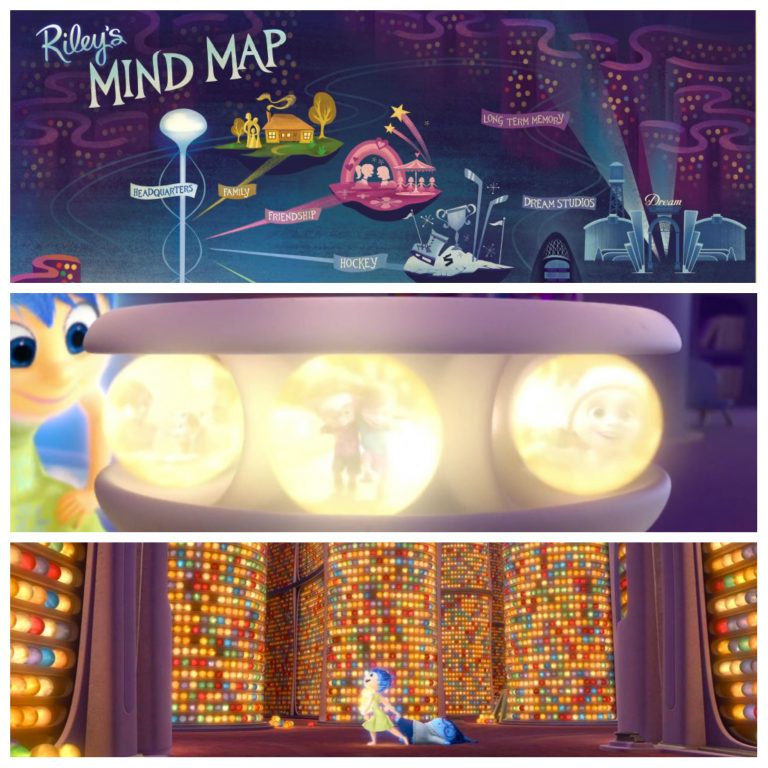

Because I sincerely believe American girls can benefit from Ghibli influence (the point of these articles), I went in search of a helpful Western analogue for Spirited Away — and found one in Pixar’s 2015 Inside Out. (Conveniently, Pixar released an Inside Out cinestory comic containing over 1,500 stills from the film that reveal countless nods to Spirited Away.)

Both animated films about a girl’s loss of identity on the cusp of adolescence, Ghibli’s Spirited Away and Pixar’s Inside Out contain a similar starting line:

Girl in the backseat of a car, nervous, mom and dad up front: they’re moving to a new town, driving to a home she’s never seen.

Upon arrival at her new house, Inside Out protag Riley learns that the family’s moving van is missing – a relatable point of stress. In Spirited Away, however, Chihiro and her parents don’t even get to their home: a tunnel too small for their car inspires an unplanned field trip on-foot – to what Dad believes to be an abandoned theme park.

Still, in both cases, two things are clear early-on: (1) our heroine is afraid; and (2) Mom and Dad will be no help – they’ve got problems of their own.

As both films take place in worlds run by spirits and emotions, audience members must suspend disbelief throughout:

Miyazaki presents elements of pure fantasy: radish spirits visit bathhouses run by frogs, heated by an arachnid boiler operator, and overseen by a bird Animagus (to borrow J.K. Rowling’s term for animal-morphing witches); a strong bath can reveal a river god inside a stink spirit; a faceless spirit can create gold, eat people…and knit. Anything goes.

Chihiro finds herself in a new place – though not the one she expected: order exists, but follows a structure she doesn’t understand.

Sometimes, s**t gets scary (i.e. running across a pipe-tightrope in the sky); other times, it’s a long wait for a train. Miyazaki makes this part of the audience’s journey, too: we experience the story as its protagonist.

The enchanted world of Inside Out is the mind of eleven-year-old Riley – but the story is about Riley, explaining Riley, analyzing Riley. Though the audience is literally inside its heroine, the adventures depicted on-screen come predominantly from the POV of her emotions. Inside Out attempts to demystify minds through five personified emotions who clarify themselves constantly.

Inside Out offers a masterfully crafted map into the minds of others, offering explanations for how characters feel and why. When Riley experiences loss of identity, it’s because the “islands” comprising her personality shut down – because “core memories” were misfiled in her mind.

Chihiro risks loss of identity, too – but, in her case, because a bathhouse witch named Yubaba took her name in exchange for a job: Chihiro – now called “Sen” (which means “one thousand”) – must work to survive in the spirit world, but recall her identity to subsequently leave it.

In both stories: a girl must struggle to retain her sense of self when placed somewhere strange, while experiencing unprecedented emotional combinations she doesn’t understand.

But Chihiro doesn’t get all of the answers about her world – she receives few, in fact. (Personally, I like to think of bathhouse witch Yubaba as a combination of Oz’s Wonderful Wizard, The Little Mermaid’s Ursula – and every exhausted-to-sanity’s-edge mother I see attempting to control babies on subway cars.)

Picking up right where the lessons of Mei leave off in My Neighbor Totoro: Chihiro excels because she makes good decisions about whom to trust in an unfamiliar place.

…My dad’s point is fair: Chihiro’s journey does feel a bit like a Japanese Wizard of Oz – but instead of red shoes and instruction to walk on a bright road leading in the direction of her desires, Chihiro’s guide (a boy with magical powers named Haku) gives her a red pill (to retain her visibility in the spirit world), and directs her in secret to a bathhouse basement to work among soot sprites.

Remember soot sprites [from My Neighbor Totoro / Chapter 2]? Promised they’d be back:

In Spirited Away, soot sprites work in a bathhouse boiler room, carrying coal to the furnaces that heat the spirits’ baths – the bottom rung of the employment ladder. Formerly soot – now equipped with energy, eyeballs and an objective (get coal into fire), soot sprites serve as low-status gatekeepers. If playing by the same rules as Totoro, Chihiro retains enough of her childhood to still see them: she also shows them respect, and appreciates their role in the operation of this magical bathhouse where she now resides. (And they return the favor by guarding her old clothes – a hint to remind Chihiro of her identity.)

Riley’s stakes in Inside Out are, in fact, much closer to Mei’s in My Neighbor Totoro: she runs away, intending to return to the family’s former Midwest home…but returns to her parents in San Francisco before her [non-cat] bus gets on I-80. Not much happens to Riley, there’s never much in the way of actual danger – but the low stakes presented are all the audience has to go on, so they become everything.

Spirited Away and Inside Out, however, both run on the same emotion-based fuel – even using some of the same stunning symbols:

Pixar director Pete Docter is no stranger to Ghibli: he translated Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle in 2004 and admits to an admiration of Miyazaki’s work – which, no doubt, inspired parts of Inside Out:

In stumbling upon the video clips above, it hit me: Inside Out doubles as Pete Docter’s user-frendly, Pixar-filtered, guide for Americans to watch Ghibli films.

Docter himself admits to experiencing confusion when watching Miyazaki’s work, ultimately surrendering to the beauty of the dreamlike worlds depicted on-screen. He also shows a “starting point” image from Inside Out of Joy and Sadness, side-by-side, riding together on a train — which smacks heavily of Spirited Away. (And Docter’s literal “into-the-woods” epiphany – that “sadness” is the film’s hero – prepares American audiences for more mature Ghibli films like Miyazaki war epic Princess Mononoke and Isao Takahata’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya and Grave of the Fireflies.)

My prediction: fans of Inside Out are likely to enjoy most of the Ghiblis, Spirited Away especially.

Embrace the “ma,” accept confusion – and get ready for the most gorgeous train ride.