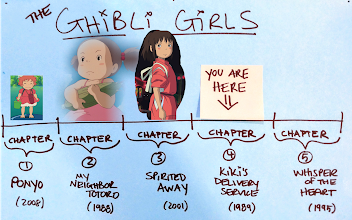

(This chapter assumes familiarity with THE GHIBLI GIRLS to this point.)

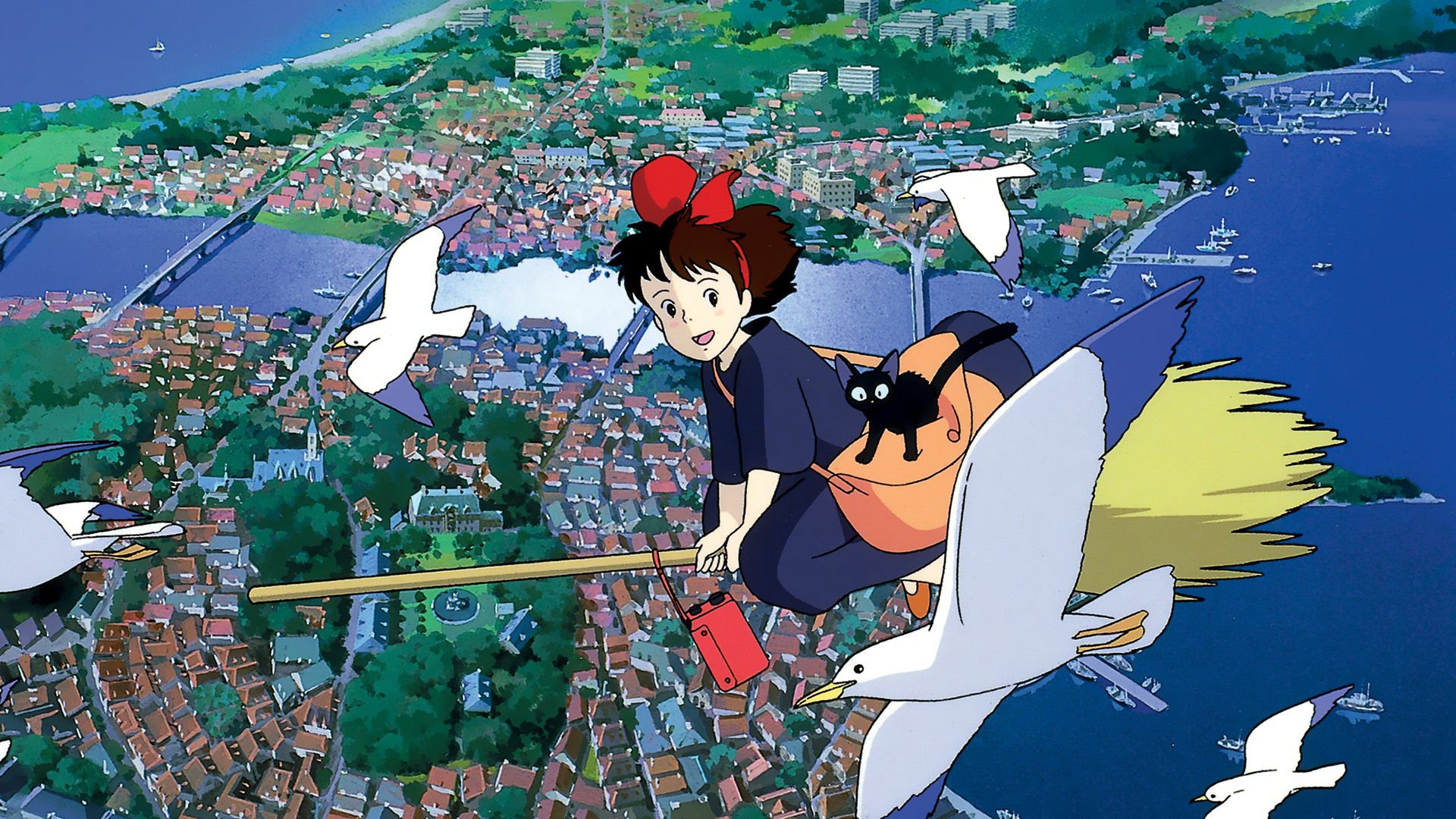

DEFYING GRAVITY

Kiki’s Delivery Service

Released: 1989 (Fun Fact: Kiki’s Delivery Service marks the first release of a Ghibli film by Disney, in 1998 – same summer as Mulan.)

Protagonist Age: 13 — same as Eighth Grade‘s Kayla Day.

Appropriate Viewing for: ALL AGES!

Miyazaki’s Role: writer/director

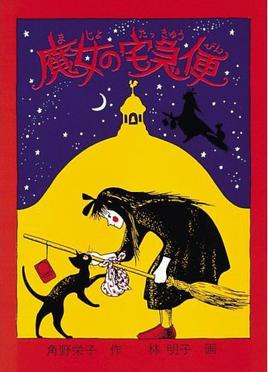

Inspiration: adaptation of Eiko Kadono’s 1985 novel, same name.

Kiki’s Delivery Service is the project Studio Ghibli took-on post-Totoro – meaning Miyazaki’s creative brain transferred straight from Mei (Chapter 2) to Kiki. (Chihiro, Chapter 3, would not come along for another decade.) Initially, Kiki was to be overseen by others at Ghibli (Miyazaki remained busy finishing My Neighbor Totoro) but, dissatisfied with Kiki’s development, Miyazaki ultimately took over lead writer/director roles there as well.

Miyazaki saw himself in Kiki, and believed he could adapt her through film as a universal guide for the grueling process of discovering personal talents and developing self-expression during adolescence (and beyond). A quick glimpse of Google search results suggests he nailed it: a staggering number of articles exist about Kiki, written in a variety of languages – predominantly female-authored. Women worldwide share their unique journeys alongside Kiki’s: the Internet reveals her to be a sort of mascot, a unifying beacon of self-belief in moments of change, transition, and uncertainty.

Returning to the initial inspiration for this Ghibli Girls series: like Kayla Day in Bo Burnham’s Eighth Grade, Miyazaki’s depiction of Kiki casts a spotlight on the power of bare sincerity inside a thirteen-year-old girl – perhaps the apex of vulnerability.

Kiki offers a one-size-fits-most judgment-free map for anyone who has ever felt in-over-their-head in the “real world.” (Reminder: Kiki’s Delivery Service is what you watch instead of the YouTube tutorials, KAYLA!)

I turn to Kiki, now, too – but this chapter isn’t about how Kiki affected me: it’s my case in support of the idea that she can affect everyone.

My theory: Kiki exists in all of us.

WE START HERE:

Kiki’s story opens with a look into the daytime sky, accompanied by a decision that today is the day to start a life-altering adventure. Immediately thereafter, she packs a bag, hugs loved ones goodbye, and – looking home straight in the eye – turns away before the opening credits have even rolled.

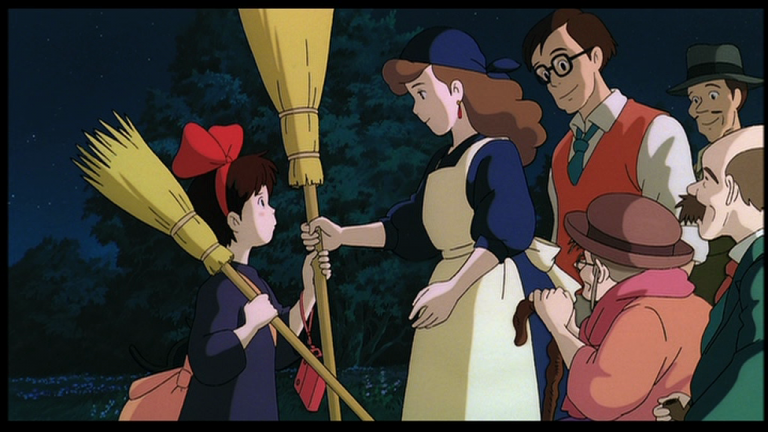

In Kiki’s case, however, “leaving home” comes via piloting a bumpy midnight takeoff out of Koriko on Mom’s broom, flying into the night:

Where Kiki differs from every one of her viewers: she is a witch – who flies. In her culture, this means leaving home on a full moon at age 13, for a year, to set-up in a new town where no other witch resides; a required study-abroad, destination unknown, without financial support from home. (Hey, Shrek only got ’till age 7.) But at its core, Kiki’s is simply a story of someone who leaves home in search of something – anything.

Anyone who has moved to “the big city” can see themselves in Kiki (including Miyazaki, apparently): new to town. Excited-and-scared. No familiar faces. No reputation. Not much money. Not sure how to transition talent into employable skill. Turning back isn’t an option.

Armed solely with her own…self, and fueled by a feeling she’s supposed to be there, confidence becomes a mandatory survival skill. In typical Miyazaki fashion, there is plenty of breathing room provided amidst the action: viewers bear witness to Kiki’s slow afternoons at work; sick days spent in bed; dinners for one, cooked and consumed at home alone.

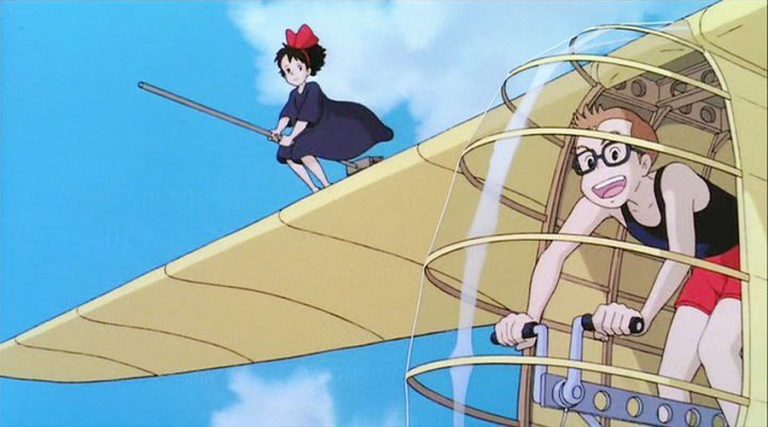

Miyazaki is quick to point out: “in [Kiki’s] world, witches are not much more talented than normal girls.” The only unusual thing Kiki can do is fly – and other characters find ways to share the airspace throughout the film: an old man living high in a clock tower is first to greet her in town; an artist out in the country greets her from a cabin rooftop; a boy her age reveals the flying bike he’s making; a dirigible comes to town and takes kids for a ride. It is quite often, in fact, that Kiki – who can fly – holds the literal lower-ground (and the lower status) in social situations.

A symbol just as universal as Kiki: the adolescent “mean girl.”

A symbol just as universal as Kiki: the adolescent “mean girl.”

An important ingredient of Kiki’s Delivery Service: Miyazaki frames “Mean Girl” as the laziest, lowest form of self-actualization – while acknowledging that, for 13-year-old girls, the Mean Girl dog whistle has the potential to overpower even the most diligent attempts by a wild heart to run free.

What makes Kiki strange to some is exactly what makes her powerful to others – but it can only do so once she learns to embrace it. And she can only embrace it through accepting it.

A recent revisit to Kiki’s Delivery Service got me thinking about other pop culture witches from stage and screen who famously fought – and won – inner-battles against seemingly endless streaks of low-status roles and senseless haters:

L to R: WICKED’s Elphaba; Buffy’s Willow; Harry Potter’s Hermione.

L to R: WICKED’s Elphaba; Buffy’s Willow; Harry Potter’s Hermione.

In the end, each in her own way, these witches crush awkward phases and learn to embrace their powerfully weird selves – earning millions of loyal fans in the process.

Through a filter of something a viewer cannot be – like a witch, masterful story-tellers can connect audiences to the parts of their personalities they often hide. Interviews with J.K. Rowling and Joss Whedon that dig into Harry Potter and Buffy character development tap frequently into the truth that coming-of-age vulnerability fueled each series. And let us not forget that Wicked bookwriter Winnie Holzman is the writer responsible for My So-Called Life protagonist Angela Chase: Claire Danes and her “Crimson Glow” hair took off from a springboard of Winnie’s words long before green-skinned Elphaba’s Broadway reign began. It may not be easy bein’ green – but the moment you accept it, maybe you can defy gravity.

Miyazaki taps into this same truth through Kiki and, in doing so, connects with audiences across age groups and cultures.

One remarkable difference separating Kiki from most pop culture witches: she shares a healthy relationship with her parents – who share a healthy relationship with one another. Miyazaki establishes Kiki’s mom and dad to be alive and well, in-the-picture and in love, at the time of Kiki’s departure: Kiki has nothing terrible to “escape.” (Not everyone does.) Kiki’s dad had been planning a camping trip for the two of them – one that Kiki’s early departure now prevents; even in the immediate wake of this cancellation, he calls Kiki “Princess” and lifts her over his head, playing airplane; he then gifts her his portable radio – that she routinely uses as her own already.

Upon her departure, Kiki’s mother offers her own sturdy broom to her daughter for the journey ahead. A reminder: Ponyo’s mom was largely absent – busy being Mother Earth; Mei’s mom was also busy – resting in the hospital (Mei brought her healing corn); and, of course, Chihiro’s mom was unavailable – cursed into pig form (Chihiro saved her). Parents, intentionally or not, teach their children how to issue spot other people (“careful the things you say”): growing up with a consistent, in-home parental presence, it is perhaps less surprising that Kiki finds trustworthy women somewhat readily upon settling into her new town.

Kiki’s Mother Figures: in-town, pregnant bakery owner Osono; in the country, a painter who lives alone in a remote cabin.

Kiki learns that adult lives can play out in an assortment of ways – and the film judges none as “right” or “wrong.” It is never called into question that Kiki collects resources from varied walks of life.

Folding into previous Ghibli Girl lessons:

Ponyo started from a place of literal magic: a young fish became a [chicken-frog, then a] girl with an assist from her sea sorcerer dad’s spilled potions. Ponyo’s story showed a child’s successful quest for self-identity and love – with reminders that chasing love comes with consequences, and miracles are possible without magic. In the end, Ponyo surrenders magic for human love. Right out the gate: love, despite its complications, is the highest calling.

Ponyo’s sea sorcerer dad, Fujimoto; Kiki’s witch mom: magic aside, parents are still parents.

Ponyo’s sea sorcerer dad, Fujimoto; Kiki’s witch mom: magic aside, parents are still parents.

My Neighbor Totoro started with the unknown of a new home – again from the perspective of a child. Mei’s story included the unknowns of Mom’s return home from the hospital, Dad’s returns home from work, Satsuke’s returns home from school. Totoro & Co. provide a comforting, if initially startling magical presence to welcome Mei to her new chapter, guiding her through the early stages of independence, but Nanny reveals an age-drawn line in that sand: magic becomes invisible over time. Mei’s world is a mash-up of the magical and the real: her manual labor in the garden brings sprouts, while Totoro inspires a gorgeous dream sequence involving sky-high trees and flight. Her rescue quest to Mom starts with practical consideration of corn’s nutrients based on Nanny’s real-world lesson – but delivery occurs with help from the magical Cat Bus.

Even if magic is only made visible through the minds of children, adult characters make clear that memories of magic remain; no character doubts what Mei sees. And Miyazaki’s gift to his audience: every viewer, regardless of age, can spot Totoro and soot sprites. Every Ghibli Girl film offers a universal portal back to its protagonist’s age – magic and all.

Perhaps, in growing up, Totoro and the Cat Bus become our real cats and dogs — and it becomes our job to navigate the dark forest and fix our mistakes.

Perhaps, in growing up, Totoro and the Cat Bus become our real cats and dogs — and it becomes our job to navigate the dark forest and fix our mistakes.

Spirited Away captures the transition out of childhood in a stunning cinematic journey through the spiritual world. We may start with a magical protagonist (like Ponyo) and the prospect of a new home (like My Neighbor Totoro) — we may even cover similar subject matter as Kiki’s Delivery Service (learning to play by new, unfamiliar rules), but Spirited Away ends where it began. Chihiro’s frame of mind changed, but not (yet) her actual life. That’s where Kiki comes in…

New Kids on the Block: Chihiro seeks work at the bath house; Kiki crash lands into her new town.

New Kids on the Block: Chihiro seeks work at the bath house; Kiki crash lands into her new town.

Kiki’s Delivery Service takes us now to the other side of childhood: it combines Ponyo’s magic, Mei’s new-kid status, Chihiro’s coming-of-age adventures – and opens the realm of romantic love.

Ghibli Girls + Ghibli Boys

Also before the film’s opening credits, Kiki expresses concerns of becoming distracted from her goals by a “boyfriend”: she wishes to put herself first – a desire a well-intentioned, flight-obsessed boy named Tombo forces her to test. (Tombo is a bit like Tony Stark, in that his superpower is his brain: he can’t fly himself, but he’ll build something that can — and confidently suit up to test it, personally. But, to be clear: Tombo is no playboy — to break it down in Eighth Grade terms, he’s a Gabe, not an Aiden.)

In Miyazaki’s films, everyone deserves a chance to fly.

In Miyazaki’s films, everyone deserves a chance to fly.

For the purpose of this series, Kiki is the Ghibli Girl whose story introduces crushes and courtship – a topic explored much more in the next chapter (Whisper of the Heart).

But this film is all about Kiki (in the way that Eighth Grade belongs to Kayla). Viewers join Kiki as she learns to adjust to magic and boys, manages a business and a budget, and finds her place in the real world – all at her pace.

Kiki starts out with the benefit of a sidekick: a talking cat named Jiji – but even Jiji eventually finds an adventure of his own (in the form of neighbor cat, Lily). Sidekicks can grow apart. Even the best friendships evolve and sometimes erode. And, apparently, even cats struggle with romance. (Side note: voicing Jiji in the English dub of Kiki’s Delivery Service became one of SNL and Simpsons alum Phil Hartman’s final projects – Disney premiered the film at the Seattle Independent Film Festival just four days before Hartman’s shocking and untimely death.)

More than any other, Kiki is the Ghibli Girl I wish I’d had when living out its protagonist’s age:

At 13, I, too, studied abroad for the first time, sans parents: Mexico, 1997. (Result of a new, young, passion-driven — and arguably naive — foreign language teacher at my middle school who shepherded a group of us over an extended Easter break.)

Early on, my clothes were stolen from my locked hotel room by a maid – who wore my Old Navy shirts in my presence to taunt me, (or so I was convinced). On a day-trip to Teotihuacan, I found myself atop of the Pyramid of the Sun when a thunderstorm hit without warning: I crawled down to safety, on hands and knees, through heavy rain and lightning strikes. On my last night, I jumped off a [second floor] balcony — to avoid breaking the piece of Scotch tape placed by a chaperone’s hand at “curfew”: I’d wanted to “go explore”…at 2AM…in a foreign country…where I barely spoke the language – and was a 13-year-old girl. (Miracle: I returned home without incident, just before sunrise, by climbing up a pipe — to avoid breaking that Scotch tape “seal.” It worked.)

I was curious, reckless, unprepared, and desperate to “fit” into the world around me — whether in the halls of my Midwestern Middle School, or the streets of Mexico City.

…But Disney wouldn’t release Kiki’s Delivery Service until the following summer. (And so, my “new witch in town, coming-of-age” movie needs were met, instead, by The Craft — a cult classic I stand-by to-date, albeit a far cry from Ghibli Girls material. An article for another time.)

I’ll stop here: as promised at chapter outset, this isn’t about Kiki and me – it’s about Kiki and you. Stories and symbolism aside, girl power is universally powerful – and Kiki’s Delivery Service is a universally good movie.

Next – and final – chapter: a return to love, this time on the other side of childhood.