Tony Award-winning Broadway Producer Ken Davenport sends me several emails a day – mass emails, nearly all containing the hashtag #5000BY2025. Translation: he aims to help produce 5,000 projects by 2025.

He’s serious about it, too: Ken hosts conferences, manages blogs, writes articles and books – and, straight from his own bio, “ma[kes] headlines by doing @#$% that other people don’t.” (My personal favorite: a heroic commitment to Deaf West Theatre’s stunning 2015 revival of 2006 Tony Best Musical winner Spring Awakening – which Davenport helped bring to a Broadway stage in record time.)

Ken Davenport’s latest Broadway endeavor: Gettin’ the Band Back Together, a musical comedy derived largely through improv. A six-year experiment, Davenport partnered with Tony Award-winning director John Rando (Urinetown) and a troupe of twelve writer-performers called The Grundleshotz (including some of the voices that developed the Tony Award-winning book of The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee). The Grundleshotz improvised the story’s script over a four-year process.

Gettin’ the Band Back Together opened last week to mostly negative reviews – which I’m not going to discuss. (You are free to Google.) Advertisements for the show treat audience member tweets as pull quotes – also not to be discussed here (suffice it to say: never a good sign).

I gave Gettin’ the Band Back Together a standing ovation, and I meant it — which I am going to discuss, candidly.

© Tricia Baron

© Tricia Baron

But first – as a showing of good faith:

Admission of Bias #1 (there will be several): I am a music improviser – I literally left my law career, in part, to complete The Second City’s Music Program and hone skills to develop musical theatre through improv. I’ve improvised more than a hundred musicals, hundreds more songs, and –

Admission of Bias #2: I am currently writing my first scripted musical (with my partner – who worked as a Second City Music Director for 15 years, pre-Broadway). Down the line, we will seek producers for this work.

Admission of Bias #3: Ken Davenport is a producer on my partner’s current show (School of Rock).

Admission of Bias #4: I know – and like – an actor in Gettin’ the Band Back Together. (I also happen to think this actor is great in the show.)

Admission of Bias #5: my dad and brother are both Kens – and I love them both dearly. (Unrelated to #1-4, but bias nonetheless.)

…Five feels like a good place to stop. (I believe I’ve established bias.)

And now, my thoughts on the show:

Gettin’ the Band Back Together is a bold, monumental – and necessary, if awkward step towards infusing Broadway-caliber musicals with improv’s raw magic. Like buying braces for a mid-puberty middle schooler, investing in improvisers to build a Broadway show is a tough sell at the outset: it’s gonna be unattractive and messy for a while – in public, no less – but, long-term, it’s a life-altering net-positive. (Assuming, of course, you’re willing to put in the work.) It’s Chelsea during the Clinton Administration: authentic and awesome – but most can’t see that yet. They stop at frizzy hair and a metallic mouth.

Speaking of frizzy hair and metal, a show that found success in this experimental section of the rock musical mosh pit is Rock of Ages. (This is a vibe Ken Davenport is clearly trying to capture, based on the casting of many show alums — including its original stars Mitchell Jarvis and Kelli Barrett.) But Rock of Ages had the nostalgia-rooted advantage of a soundtrack comprising ’80s Billboard megahits: audience members arrive with preestablished emotional connections to songs like “Sister Christian” and “Cum on Feel the Noize.” Unfortunately, Gettin’ the Band Back Together cannot offer “[American Childhood in Rock Songs]” – and the powerful combination created in the intersections of music and memory proves ever-elusive to engineer, even for masterful rock musical composers like Tom Kitt (whose High Fidelity is, in my opinion, the best attempt to-date at a rock pastiche score that sounds like your childhood).

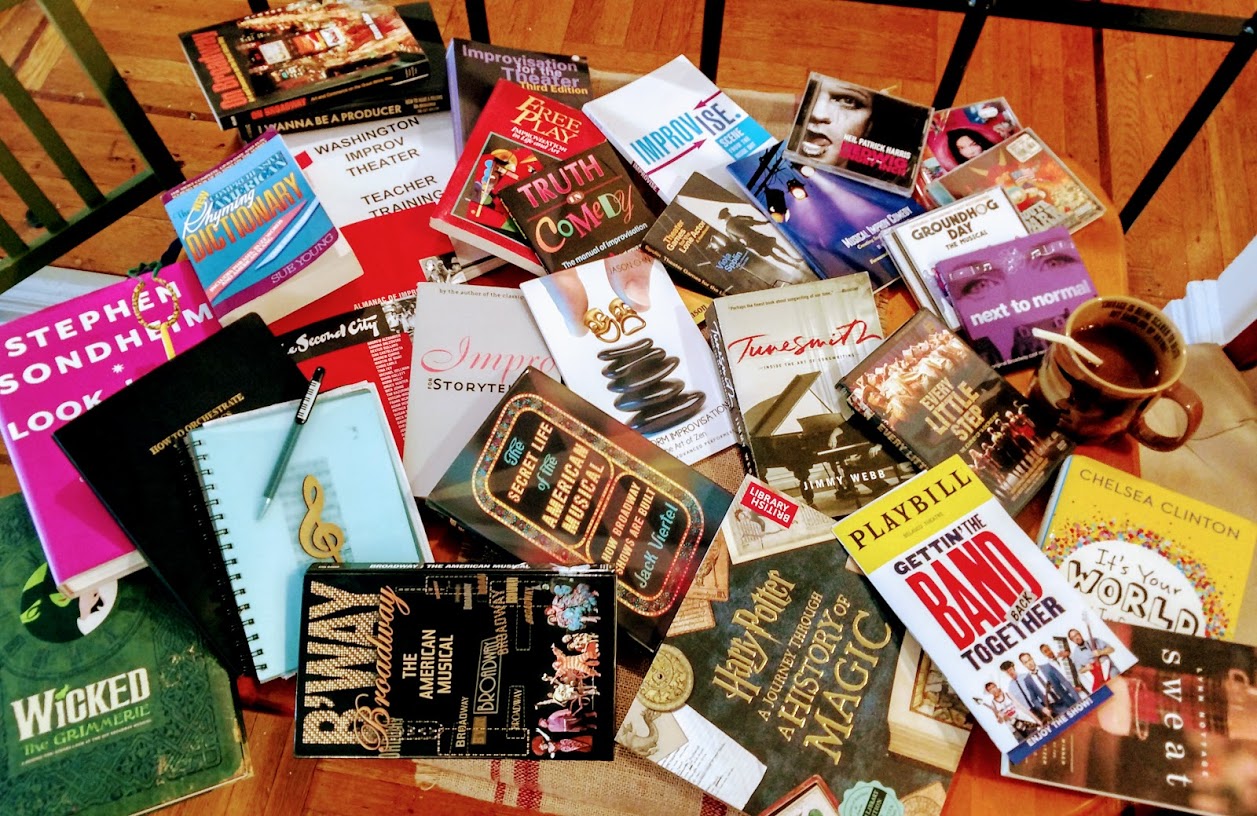

I decided to write this article while watching an Amy Winehouse documentary and reading the British Library’s Harry Potter: A Journey Through a History of Magic. Both “inside looks” revealed evidence of a gifted writer’s unfiltered mind – including pages of each artist’s handwritten, half-baked ideas: creative genius peppered with possibly slipping sanity, side-by-side, sometimes in the same sentence.

All who create carry the baggage of archives that appear to be laced with “crazy”; no first draft finds its second without it. We who create in pre-established mediums have the luxury of looking to the work of those who went before, leaving breadcrumbs back to reality (if desired). But to create where there’s no road…?

Such is the marrow of improv: bare black boxes (or bars, or apartment living rooms) where artists create on the fly, building and listening and building some more. Roads come and go.

This is, in fact, familiar terrain for Ken Davenport: his very first foray into producing, The Awesome ‘80s Prom, used improvisation to develop its script – and ran Off-Broadway for a decade, returning an impressive 500% to its investors.

Evidence of great improv comedy can be found throughout Gettin’ the Band Back Together: perfect nemesis band name – coupled with solid jingle callback; some stellar one-liners (no, I’m not about to spoil them); a belly-laugh inducing second-act bit involving mic stands and a minibike. But the engine of improv is ephemeral – even more so than musical theatre – and its uncooked energy only goes so far upon application to the algorithm of Broadway.

In The Secret Life of the American Musical: How Broadway Shows are Built, Jujamcyn Senior Vice President Jack Viertel presents this equation piece-by-piece, Overture to Curtain Call. He begins his chapter on Opening Numbers with a quote from City of Angels director Michael Blakemore: “when the curtain goes up, the audience is in trouble.” The point: upon entering the new world of a musical, it is crucial to greet the audience appropriately and set expectations. Gettin’ the Band Back Together accomplishes this with a literal greeting: a pre-show curtain speech that labels upcoming content as a “totally original musical.”

But improv is a slippery source for “originality”: improvisers draw from their own experiences – which, inevitably, if unconsciously, include the art that inspired them. Despite its pre-show claim of total originality, Gettin’ the Band Back Together borrows everything from costume pieces (#youwillbefound) to iconic choreography (#stepkickkickleapkicktouch) to deep-cut character bits from Broadway canon. And it doesn’t stop at Broadway: a doppelganger of Ben Stiller’s White Goodman (Dodgeball) features, as does Daniel Stern’s emotional climax from the 1991 comedy City Slickers. (#DOover)

A student of both Broadway musicals and improv, I perceived a show that would benefit from a recalibration of what it heightened from source material. (And I get the sense there was no shortage of comedic source material from which to draw.) As it stands, I saw potential for Gettin’ the Band Back Together in land of guilty pleasures – Broadway’s Snakes on a Plane, if you will – had it pushed full-throttle into its jokes and abandoned the emotional parachutes of its non-comedic ballads. Samuel L. Jackson did not need a sub-plot involving home foreclosure to sell Snakes on a Plane. We were all there for one thing: to watch him get those snakes off that motherf**king plane. (Let’s just get the f**king band back together!)

My message to Ken Davenport and his group of improv superstars: KEEP GOING. Dare to delve further in this direction: I’m in – and, for what it’s worth, so are my seat-neighbors. (I watched Gettin’ the Band Back Together directly in front of some ladies celebrating a 40th Birthday, living their best lives, behaving in a manner inappropriate for a typical Broadway house – but one that didn’t distract in this room. As I’ve written previously, I am all about expanding the pool of Broadway patrons.)

I witnessed a show that filled its tank with the wrong octane fuel, but presented itself on a Broadway stage anyway (because, with Ken Davenport in the driver’s seat, it could), allowing others – like myself – to benefit from the experiment. For that, I am deeply grateful.

Gettin’ the Band Back Together gave my partner and me so many ideas – ideas we, ourselves, can’t (yet) afford to develop fully. So, in the meantime, we study: we attend every show we can afford, staying out late post-show with friends and fellow theatre-goers to discuss; we revise outlines and make plans – our scale of “EAIs” (Easily Actionable Items), to use Ken’s own term – and we continue to brainstorm with the benefit of fresh examples, including those that flop.

Building the bridge between Broadway and improv requires quarterbacks like Ken Davenport: unestablished producers with shallower benches (and pockets) can’t risk their Rolodexes (nor bankroll the inevitable flops). Davenport rules an empire with players in every position on the board, a billion customized blogs – and a hashtag he actually means.

Ken Davenport is very close to unlocking math that can catch the improv genie in the Broadway bottle. If successful, he can fundamentally change how we write the American musical — for the better.

I believe firmly that musical improv has a place in the future of American Broadway. I’ve seen glimmers of it – I’ve even been lucky to be part of a few. I believe there is a Prom Queen to be found on the other side of the gawky adolescence that is Gettin’ the Band Back Together. (Davenport has had good luck with proms…)

At bottom: I believe well-intentioned gawky adolescence placed in the public eye deserves a sincere standing ovation – and I look forward to its persistent evolution.

Other JMSunderduress articles you may enjoy…

RODGERS & HAMMERSTEIN’S CAROUSEL: IF I REWROTE YOU