Dedicated to Grandma Mazer.

If Rodgers & Hammerstein’s 1945 musical Carousel is unfamiliar territory, fear not! This article is beginner-friendly — and addresses a larger issue: what to do with a piece of beloved art…that’s also profoundly problematic.

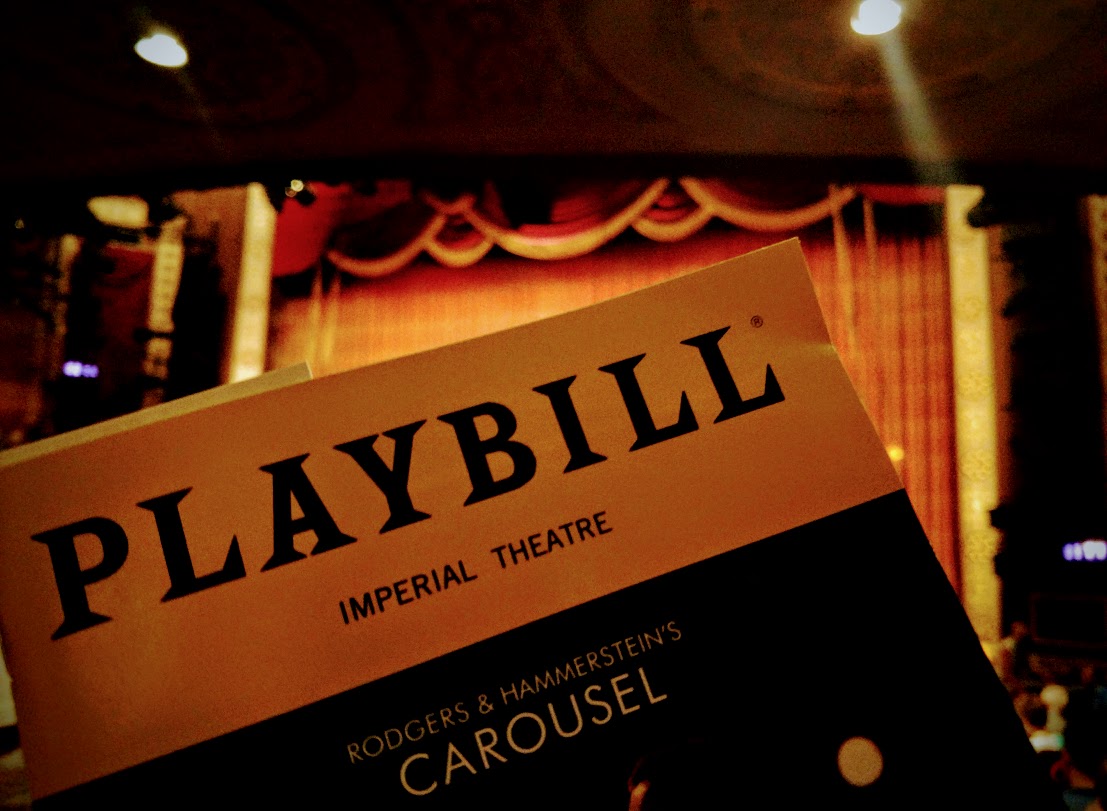

Recently I swooned, cried, and cringed my way through the 2018 Broadway revival of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel, set to conclude its run shortly (September 16). A favorite musical score among three generations of my family members – myself included, this marked my first viewing of the show as an adult.

I find myself deeply conflicted – justifiably so: Carousel is, among other things, a Broadway classic with beautiful ballet, a sensational score…tied together by a book about wife beating and undeserved redemption. Oy.

A BRIEF, PARTIAL SUMMARY:

(Carousel opened 73 years ago: at this point there’s nothing to “spoil.”)

An adaptation of Ferenc Molnár’s 1909 play, Liliom, Carousel starts on the coast of Maine in May, 1873. Mill worker Julie Jordan falls for amusement park carousel barker (and ladies’ man) Billy Bigelow: the romance costs both their jobs – and Julie her residence. She moves in with her cousin, Nettie Fowler. Time passes: married, poor, and desperate, Julie reveals to her best friend and former co-worker (Carrie Pipperidge) that Billy has hit her. Julie has no intention of leaving: she loves Billy – who now spends most of his time with full-time whaler/part-time con man Jigger Craigin. Jigger convinces Billy to assist in a robbery [of Julie’s former employer, Mr. Bascombe]. Added pressure: Julie’s pregnant – Billy’s gonna be a father.

The robbery goes awry and Billy commits suicide to avoid capture. Stuck at heaven’s back gate, Billy demands judgment from “The Highest Judge of All”: in the meantime, 15 years have passed “down here” and Billy’s daughter, Louise, is an angsty teenage outsider, snubbed by New England society – including Carrie’s children. Billy gets a day to return to Earth and make things right: he visits Louise on her graduation day…and hits her in a moment of frustration. He vanishes, ashamed – then, in the final scene, crashes her graduation, invisible: a speech – delivered by someone else – shares inspiring words that move Louise, Nettie, and Julie to join in song. (Billy’s there, too: invisible still, but also affected.) END OF SUMMARY.

That’s right: Billy Bigelow hits his wife, knowingly attempts a robbery, commits suicide, demands a personal audience with God at the pearly gates – to include one-on-one feedback about his [unquestionably immoral] actions on Earth, returns from the dead – hits his daughter, and is…redeemed by one of the most gorgeous musical theatre finales to-date?! As stated at the outset: I find this problematic.

I’m going to give Carousel enthusiasts the benefit of the doubt: I don’t think anyone falls in love with the show because Billy hits Julie – I don’t think audience members buy a ticket itching for that part of the story (and anyway, it’s never shown). Like Julie, fans find mind-bending ways to justify significant flaws in something/someone they love.

…But should we?

ISSUE #1: CAROUSEL’S TREATMENT OF DOMESTIC ABUSE LEAVES MODERN AUDIENCES WANTING.

BEN BRANTLEY’S NYT REVIEW: “The mother-daughter dialogue that falls so abrasively on contemporary ears — about it being possible to be hit loud and hard and ‘not hurt you at all’ — is delivered quietly and unconvincingly, almost as if hoping to pass unnoticed.”

That’s right: mother-daughter dialogue about being hit by someone you love and having it “not hurt.” Oh, Carousel: why must your score sound so good – good enough to resurrect an upsetting book on a Broadway stage in 2018? WHHHHHHHY?

To be clear: I’m not against tackling the issue of domestic abuse on the stage, only that –

ISSUE #2: THE ABUSER IN CAROUSEL IS UNWORTHY OF THE REDEMPTION HE RECEIVES FROM THE SHOW.

BEN BRANTLEY’S NYT REVIEW: “I always squirm through the undeserved uplift and optimism of the final scene, and this time was no different.”

Why is Billy Bigelow’s a redemption story worth amplifying amidst the #metoo movement – or any time, for that matter? WHHHHHHHY? Now, take The Shawshank Redemption’s Andy Dufresne: s**t-stained, soaking wet, arms raised in the midnight rain after nearly two decades of unjust incarceration – that’s redemption earned. In Carousel, apparently it is enough just to mean well. What has Billy Bigelow done or learned?

My “Want”: a different book for Carousel – one with zero wife-beating.

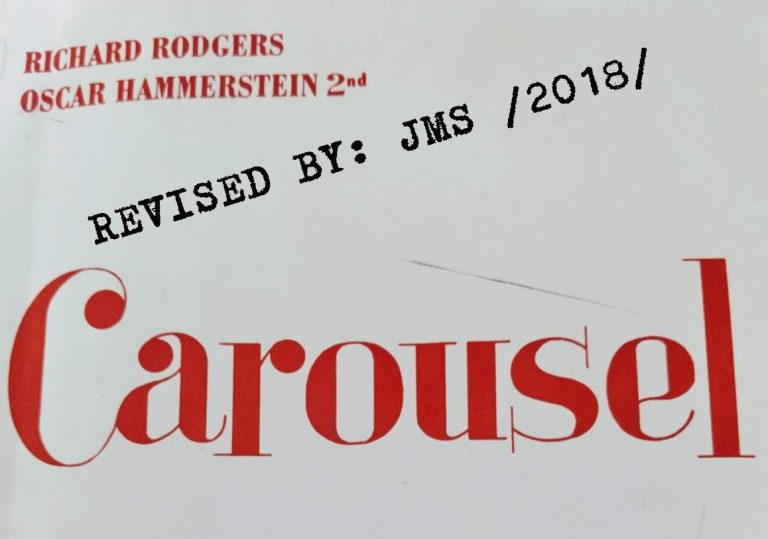

RODGERS & HAMMERSTEIN’S CAROUSEL: ADAPTED BY JMS

Not one to let my “golden chances pass me by,” I’ve re-imagined one. Immediately below, I’ve listed Carousel’s scenes and musical numbers – with my *CHANGES* and CUTS labeled (there are only 7).

ACT I

SCENE 1: An amusement park on the New England coast. May. Late afternoon.

Prelude: “The Carousel Waltz” (instrumental) – Company

Movement and music establish Billy; Julie/Carrie friendship; Julie/Billy courtship – CLASSIC.

SCENE 2: A tree-lined path along the shore. A few minutes later, near sundown.

“You’re a Queer One, Julie Jordan” – Carrie & Julie

Carrie calls out her best friend’s curious behavior/crushing on Billy – fine.

“Mister Snow” – Carrie

Carrie tells Julie about her new fisherman fiancé, about whom she’s severely smitten – fine.

“If I Loved You” – Julie & Billy

Billy + Julie = love, for better and for worse (foreshadowing worse) – CLASSIC.

SCENE 3: Nettie Fowler’s spa on the ocean front. June.

“June Is Bustin’ Out All Over” – Nettie, Carrie & Company

Summer’s here; everyone’s horny – CLASSIC.

*CHANGE #1* – BILLY DOES NOT NEED TO HIT JULIE FOR THIS SCENE TO LAND:

Julie confides in Carrie that she and Billy are broke and frustrated; he hates staying with Cousin Nettie (no change there). Despite his efforts, Billy can’t find work: he hangs around Jigger Craigin to make connections with the other whalers – though Julie distrusts Jigger (again, no change there). She’s scared about the future, tensions are high, Billy can be short-tempered: blue collar life is hard – on top of that, Billy is a complicated man to love.

All of this is, in itself, perfectly valid – and powerfully relatable for an audience in any era.

(If incorporating the subject of domestic abuse feels absolutely necessary, perhaps Billy can be the one who grew up on the receiving end of it – and does not wish to carry forward that piece of his own father’s legacy. Give him a version of a line from the Finale’s graduation speech somewhere in here, in passing (simultaneously foreshadowing): perhaps, “world belongs to me as much as to the next fella.”) *END OF CHANGE #1.*

“Mister Snow” (reprise) – Women, Julie, Carrie & Enoch [Snow]

Anticipation of Carrie and Mr. Snow’s wedding – fine.

“When the Children Are Asleep” – Enoch & Carrie

Carrie and Mr. Snow dream together about the family they will build – fine.

“Blow High, Blow Low” – Jigger, Billy & Men

Whaling’s important in this world: let’s see more of what that looks/sounds like! – CLASSIC.

*CHANGE #2* – INSTEAD OF JIGGER *AND BILLY* PLANNING A ROBBERY:

Scene following “Blow High, Blow Low” still starts with Jigger plotting to rob Mr. Bascombe – but with someone else: a fellow full-time whaler/part-time con man, for fun – and clarity, let’s call this character Ficsur (the “Jigger” of Molnár’s Liliom). Ficsur is the ringleader of this crime – he brought Jigger in.

Jigger and Ficsur decide that, to pull off the job proper, they need a third man, a lookout: Jigger suggests Billy – who he knows is desperate for work. Jigger sells the job to an initially reluctant Billy as “doin’ a bro a favor”: he peer pressures him into it – which works, in the immediate wake of Julie’s announced pregnancy. Jigger assures: Billy will serve solely as a lookout. *END OF CHANGE #2*

Springboard of Billy desperation preserved for:

“Soliloquy” – Billy

Billy contemplates impending fatherhood/his own life choices – CLASSIC.

ACT II

SCENE 1: On an island across the bay. That night.

“A Real Nice Clambake” – Company

*CHANGE #3* – NO ONE CARES ABOUT YOUR G*DD*M CLAMBAKE, COUSIN NETTIE:

Keep the start of the entr’acte music (which reminds audiences of “Soliloquy”/where we left off in the story) – extend it even, but then jump straight to location of SCENE 2: Mainland waterfront.

Jigger, Ficsur, and Billy make final arrangements for the robbery – to occur at any moment. Billy has cold feet; Ficsur threatens him. When Bascombe arrives, things immediately go awry: Ficsur initiates stick-up, Bascombe has a pistol and shoots him; Jigger flees (as does Billy from his lookout post). Police arrive, responding to the gunshot: they see only one man’s backside in the darkness – Billy’s, and shoot him. Jigger witnesses this and continues to flee. Bascombe gives his statement about the attack: two men jumped him – which is all he saw. (Police assume: Ficsur and Billy, both now dead.)

Bascombe is puzzled, though: he could swear Billy wasn’t one of the two men who jumped him (he recognizes Billy: they met in Act 1, Scene 2). …Maybe there’s more to the story – though police know Billy’s wife was pregnant/he was desperate. Ficsur is also a known felon. It’s an open-and-shut case: Billy was in on it – he dies a thief. *END OF CHANGE #3.*

Late for Act II*? Re-enter the story with Julie, at Billy’s funeral (or just after):

“What’s the Use of Wond’rin” – Julie & Nettie

Julie’s conflicting emotions about loving a flawed man – CLASSIC.

*CHANGE #4* – now sung at (or after) Billy’s funeral; his eulogy. No longer suggesting abuse, but instead wrestling with the uncertain final moments of Billy’s life: she is desperate to believe there’s more to the story… After all: where is Jigger? *END OF CHANGE #4.*

“You’ll Never Walk Alone” – Nettie

Nettie consoles Julie – CLASSIC.

*Side note (pet peeve): I’d love to stop rewarding the bad behavior of Act 2 latecomers, denying them nothing of the story…while making those of us who were punctual sit through a meaningless “Clambake.” (I know I’m in good company: there is a Cole Porter story on this very subject, from 1929’s Fifth Million Frenchmen – in which he purportedly placed his best two numbers in the show early-on, intentionally to encourage audience members to be better about timeliness.) …But back to the show:

SCENE 3: Up there.

“The Highest Judge of All” – Billy

*CHANGE #5* – INSTEAD OF “UP THERE”/BILLY DEMANDING AN AUDIENCE WITH THE LORD:

In my version, Billy doesn’t get a scene – and song – to mansplain his way to a private audience with God. In 2018, I can’t bring myself to reward a character’s (or person’s) demands for a moment they haven’t earned with extra stage time in an already long show. I’m done rewarding bad behavior. I’m done listening to the unfair reasons life was hard to explain bad behavior. Everyone’s life is hard.

CUT. IT. OUT.

(I realize this scene arose from a need for additional time to change elaborate sets [in 1945]. I am told today’s technology eliminates need for this much time. If more time needed pre-ballet, extend Billy funeral: have Carrie reprise “What’s the Use of Wond’rin,” addressed to Julie – since “What’s the Use of Wond’rin” changed to Julie’s solo [above].) *END OF CHANGE #5.*

SCENE 4: Down here. On a beach. Fifteen years later.

…Because I’m coming up with these rewrites largely on the fly: 15-year passage of time [explained in the scene I’ve cut] to be accomplished instead with a “Fifteen Years Later…” projection. Done.

“Ballet” (instrumental) – Louise, Fairground Boy & Company

As described in the original book below – CLASSIC – and can stay the same! (OR, *POSSIBLE CHANGE*: incorporate Billy’s ghost into the ballet somehow if that feels necessary…)

“The daughter, Louise, is discovered standing alone on the beach in full morning light. She runs and leaps and tumbles in animal joy. She turns a somersault and lies down on the sand to stare at the sky. Two ragged urchins come in leap-frogging. She joins them in their rough play. Mr. Snow enters followed by six little Snows in Sunday hats in single file. They stop in amazement to see the boisterous rough-housing of Louise and her companions. Mr. Snow strongly disapproves. Louise asks them to play with her. They snub her and leave. A younger Miss Snow lags behind out of curiosity. She examines Louise’s poor dress and bare feet with unfriendly dislike. Miss Snow is stuck up. The children speak:

MISS SNOW: My father bought me my pretty dress.

LOUISE: My father would have bought me a pretty dress too. He was a barker at a carousel.

MISS SNOW: Your father was a thief.

Louise chases her in a rage and steals her fancy hat. The boys approve. A carnival troup comes in, headed by a young man who is like what Louise believes her father to have been. She is enchanted and excited by their costumes. She snitches the gold parasol of the leading acrobatic lady. The carnival people perform a brutal and frenetic Waltz. The acrobat lady sees Louise holding the stolen parasol and demands it back. The young man and Louise meet face to face. He tells her not to mind and winks at her. The carnival people exit. Louise is on the beach with the young man who has waited behind. He makes love to her. In spite of herself she is drawn toward him. He grows frightened at her intensity. Realizing she is only a child he leaves her and goes away. She feels humiliated and ashamed. She weeps. A children’s party comes in dancing a Polonaise. She tries to join them but is constantly pushed out. Louise tries to play by herself outside of the party. Her heart breaks. Miss Snow makes fun of her. All the children begin to mock. Louise turns to them in desperation. They are frightened by her fury. She whispers: LOUISE: I hate you! I hate all of you!

The children continue dancing oblivious to her agony. She is an outcast.”

SCENE 5: Outside Julie’s cottage.

*CHANGE #6* – JIGGER RETURNS

It’s still Louise’s graduation day – she’s grown-up exactly the same: father dead before her birth, leaving behind a reputation notorious enough to set a foundation of shame for her life of ceaseless torment. In my version it’s not a ghost dad who appears before her, trying to fix the wreckage he left behind, but flesh-and-blood-Jigger – who has returned to tell Julie (and her) the truth about Billy’s death. Afraid, Louise calls for her mother –

Julie comes to check on her troubled daughter, who [still] storms inside – leaving her alone with Jigger, whom she recognizes immediately. Jigger reveals the truth about Billy’s death: he offers to try and clear Billy’s name – which Julie considers, but ultimately refuses; it wouldn’t change anything. The important thing is that she and Louise know the truth. Jigger then leaves Julie alone on-stage. /

/ At some point during all of this, Billy’s ghost appears on-stage – though not visible to Julie or Jigger.

Alone (or so she believes), Julie delivers a short monologue – addressed to Billy. He responds, though not visible to Julie, in song. She can only sense his presence: *END OF CHANGE #6*

“If I Loved You” (reprise) – Billy

Billy’s ghost serenades Julie – CLASSIC:

Julie! Julie!

Longing to tell you

But afraid and shy

I let my golden chances

Pass me by

Now I’ve lost you

Soon I will go in the mist of day

And you never will know

How I loved you…

SCENE 6: Outside a schoolhouse. Same day.

Finale: “You’ll Never Walk Alone” (reprise)

*CHANGE #7* – HAVE NETTIE STEP-IN TO DELIVER GRADUATION SPEECH THAT SETS-UP FINALE:

Keep text exactly as is, but the character set to deliver speech (i.e. Dr. Seldon) falls ill and Nettie must step-in last minute (she’s the one people turn to in such moments): she can’t read the handwriting of the prepared speech, so she wings it.

Here is the speech text:

[NETTIE]

I can’t tell you any sure way to happiness.

I only know that you’ve got to go out and find it for yourselves.

You can’t lean on the success of your parents. That’s their success.

And don’t be held back by their failures.

*CHANGE #7.5* – Billy’s ghost appears on the line “and don’t be held back by their failures.” Maybe he takes over parts of the speech/overlaps with Nettie (or, at least that’s how it appears to Julie and Louise):

Makes no difference what they did or didn’t do.

You just stand on your own two feet.

The world belongs to you as much as to the next fella

Don’t give it up, an’ try not to be scared of people not

Liking you, just try likin’ them. Just keep your faith an’

Courage an’ you’ll come out right. It’s-It’s like what

We used to sing ev’ry mornin’ when I went to school, maybe

It’s still the same, I don’t know… *END OF CHANGE #7.*

…And then the finale happens largely the same (with the gorgeous “You’ll Never Walk Alone” reprise), but Billy kicks it off, addressing his wife and daughter, joined almost immediately by Nettie. The good harmonizes with the bad. (That’s life.) We end the show from the shared POV of Julie and Louse, not Billy. Julie and Louise are what give Billy this power: an invisible moment of forgiveness/family reconcile.

END OF SHOW.

This is the Carousel I see in 2018: still drenched in the timeless, toxic masculinity of a character who would rather become a criminal than ask for help – but sans spousal abuse. A stripped down revisit to the show’s springboard of jobs lost for love (Act 1, Scene 2) reveals the tragedy of Carousel as one born from capitalism and circumstance – which is also timeless.

My Carousel reboot keeps the Act II spotlight on the ladies – where I think it begs to belong. And looking to Les Misérables (among others), introducing ghosts in a musical’s Finale requires no lengthy leadup: another long show, no one stops to question Fantine and Eponine showing up for the final number – they just do and we all cry and we’re all better for it. Just part of the magic of musical theatre.

(…sigh…)

Like the Smashing Pumpkins musical I outlined recently, this has been a fun exercise. I recognize, of course, that it comes from a selfish place: I don’t want to see Carousel vanish into the archives of unusable Broadway shows – which, on plot alone, I kinda think it should. If anything, I want to see Carousel’s fan pool grow and diversify (why I’m writing about it) – and I think this revival’s producers did, too, based on choreographer and casting choices.

It’s a tall ask, though, getting Broadway newcomers to the box office with a show tracking a wife beater’s unearned redemption – even if it’s set to one of the greatest scores of all time. And even if it showcases diverse faces with saintly voices – plus an international opera superstar (Renée Fleming) and a “hot” ballet choreographer (Justin Peck) with major cred in current culture beyond Broadway’s borders. Even then.

I so want Carousel to live on for future generations: I feel lucky to have heard it in 2018, on a Broadway stage, performed by a gifted cast. Maybe it’s nostalgia: I grew-up singing You’ll Never Walk Alone alongside my own mother and grandmother. But nostalgia or no, going off what I felt last week, Carousel itself – in its current form – feels a bit like a ghost grabbing a moment of redemption that maybe, just maybe, it didn’t quite earn. (See also Finian’s Rainbow, 2009 Broadway revival – which Green Day’s American Idiot replaced, coincidentally.)

When it comes to problematic theatre from our imperfect past, keeping Broadway’s focus on new and diverse voices (which I believe is the correct direction) leaves little time to resuscitate white-man compositions from the 1940s. Rodgers & Hammerstein don’t need more money – they’re set (also, dead). But one strategy I think merits more attention: pushing the practice of hiring diverse writers – ideally women (the dream) – to develop updates to musicals with powerful scores. Like the reconstructive script surgery Peter Stone performed on Irving Berlin’s 1946 Annie Get Your Gun, (backed smartly by Barry and Fran Weissler to prepare for a Bernadette Peters-led 1999 revival). Or David Henry Hwang’s 2002 rewrite of Flower Drum Song (1958) –another Rodgers & Hammerstein. …Or like I’ve done here. (I’m available.)

Acknowledgment: I received invaluable dramaturgical assistance for this article from my amazing mother, who dug through chests of her music director mother’s old sheet music/notes, relaying portions like a pro. I’ve said it before: the love of musicals in my family spans several generations and runs deep – “deeper than a well,” one could say (or sing).

More JMSunderduress you may enjoy…

THE GHIBLI GIRLS: A SERIES IN FIVE CHAPTERS